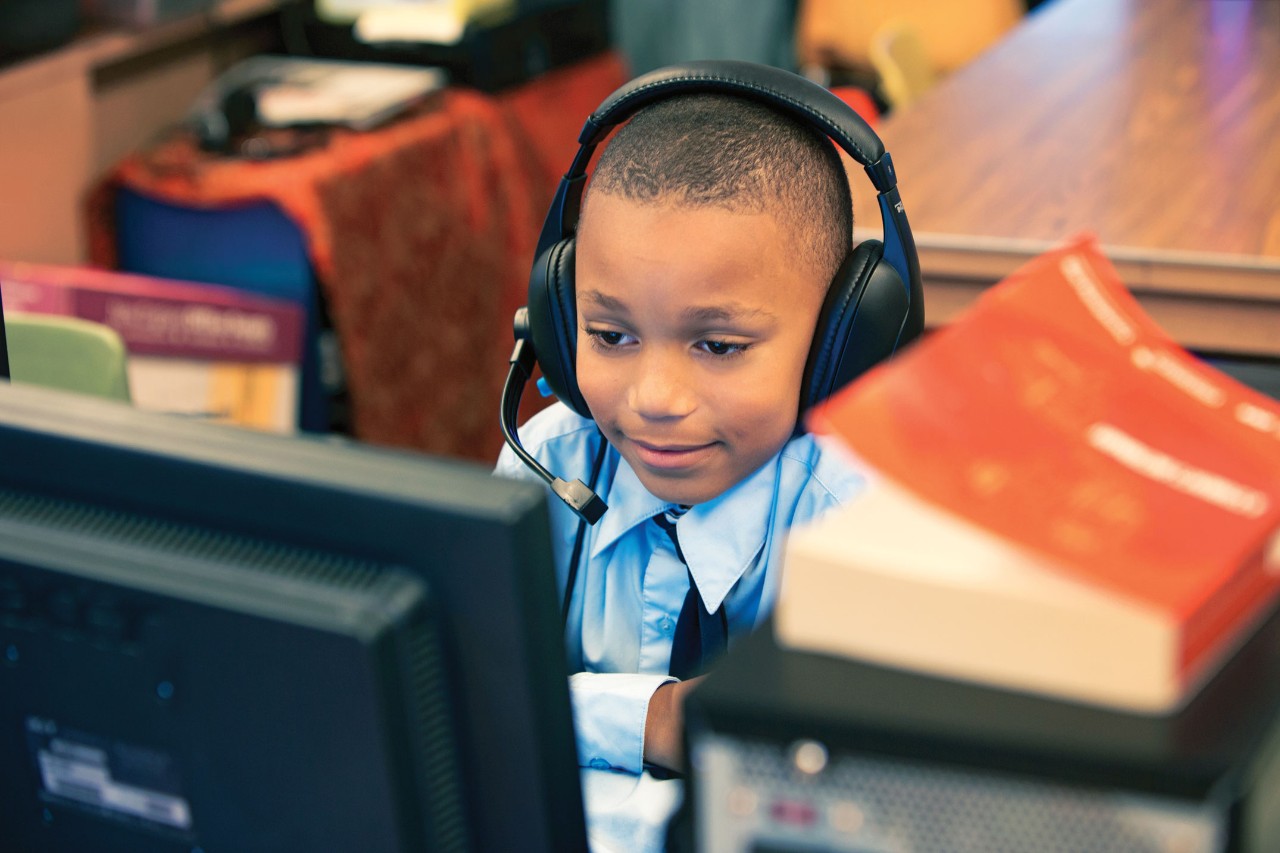

Fifteen years after its launch in eight Boston schools, the Lynch School’s City Connects now serves 30,000 low-income students in 84 schools across the country. The research-based student support and intervention program “has erased two-thirds of the achievement gap in math and half the achievement gap in English” while cutting the high school dropout rate in half at its partner schools, wrote University of California, Berkeley, Professor David L. Kirp, who praised City Connects in a recent New York Times opinion piece on community schools.

“If City Connects were a company, Warren Buffet would snatch it up,” Kirp concluded in his column, which appeared August 8—just about a month after the venture philanthropy organization New Profit, Inc., announced it was awarding a $300,000 grant to City Connects.

Rooted in rigorous, peer-reviewed research, City Connects has become a national model for supporting students in high-poverty urban school districts. The program addresses the range of challenges, such as poor healthcare or lack of enrichment programs, that studies show prevent low-income students from learning “at maximal capacity,” explains City Connects Executive Director Mary E. Walsh, the Daniel E. Kearns Professor in Urban Education and Innovative Leadership at the Lynch School (pictured, right).

“It might be a pair of eyeglasses, a tutor or mentor, or an afterschool program in the arts,” says Walsh. “But our goal is to give all our students what they need to thrive.”

City Connects’ “whole child” approach draws on developmental science research indicating that students do better in school and in life when they are educated across multiple dimensions—intellectual, social, emotional, spiritual, and physical.

Walsh says the program addresses the needs of “the great middle”—the large number of students who get passing grades but are beginning to struggle in one or two areas of development. While many programs target low-income students who are at risk academically or emotionally, she notes, “children in low-income areas who are doing okay in school have little opportunity for enrichment. Their parents can’t take them to ballet or music lessons, and they miss out on what a lot of other children have.”

Each October, 96 City Connects coordinators trained in social work or school counseling, and working inside a partner school, meet with teachers and administrators to analyze and record each student's strengths and needs in four areas: academics, health, social-emotional development, and family.

After completing the reviews, the coordinators reach out to community partners—including social service agencies, community centers, museums, universities, mobile health services, and medical centers—to match support services and enrichment programs to students. “By December,” says Walsh, “each child has a tailored plan.”

Students deemed “at risk” based on their review, she adds, receive a more intensive mix of supports and services, such as mental health counseling or more costly medical care.

With 15 years of data on City Connects participants, Walsh will now begin studying their post-secondary paths. “We keep digging and looking at the data in many, many different ways,” she says, “and the results are sturdy. Schools can really make a difference for low-income children.”

Funding for the program, says Walsh, comes from City Connects school districts, nonprofit organizations, charitable foundations, and nonprofit venture philanthropy funds, including New Profit.

In January, the Center for Optimized Student Support at Boston College released its 2016 progress report on the program, expanding its body of evidence showing that City Connects helps to significantly improve participants’ grades and test scores as well as attendance, retention, and dropout rates—both while students are in the program and after they’ve left.

Meanwhile, a cost-benefit analysis of the program conducted by the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, last year found City Connects to be cost-effective as well. The research shows that the program “costs less than $800 per student annually—about 6 percent on top of the typical cost to educate one,” Kirp noted in the Times. The program generates a return of at least $3 for every dollar spent. “Providing the program to 100 students over six years would cost society $457,000 but yield $1,385,000 in social benefits.”

—Alicia Potter