Ann Burgess has analyzed the minds of some of the world’s most infamous murderers, from Kansas serial killer Dennis Rader, known as BTK, to Ed Kemper, whose first crimes were killing his grandparents as a teen. For nearly six decades, she’s educated practitioners and students to understand crime victims—and perpetrators—beyond their violent circumstances.

Karen Pounds focuses on the therapeutic relationship between psychiatric patients, nurses, and interpreters, which she says “is the basis of healing and the work of psychiatric nursing.”

Julie Dunne emphasizes the humanity in all workers, understanding that nobody is impervious to mental illness, including health care providers. She helps them take care of their own mental health through a combination of medication and mindfulness strategies.

These three faculty members at the Connell School of Nursing (CSON) share their expertise and their commitment to prioritizing the voiceless. They do this through their clinical practice and in the classroom, educating graduate nursing students pursuing the psychiatric/mental health (P/MH) specialty. Their dedication and experience are especially needed now as the faculty prepare the newest generation of students to face growing public health crises in the U.S., including increased suicide rates, a climbing number of deaths from excessive alcohol use, and a daunting shortage of mental health professionals.

CONFRONTING THE TOUGHEST MENTAL HEALTH CASES

Professor Ann Burgess pioneered a deeply human approach to mental health by providing the context necessary to understand and make predictions about the behavior of violent offenders. She teaches popular courses in forensic mental health, forensic science, and victimology—all grounded in her intense personal experience.

In the early 1970s, Burgess co-founded one of the first hospital-based crisis counseling programs in the world at Boston City Hospital with Boston College sociologist Lynda Lytle Holmstrom, interviewing 146 victims of sexual assault ranging in age from 3 to 73. Their resulting American Journal of Nursing article, “The Rape Victim in the Emergency Ward,” was a multidimensional portrait of these victims that outlined their emotions, from anxiety to humiliation to self-blame.

Based on Burgess’ victimology work, the FBI asked her to consult on behavioral patterns among rapists and serial killers. Lawyers began to consider her a key part of their teams, too, bringing her into the fold as an expert witness on high-stakes cases. In 2016, she was named a Living Legend by the American Academy of Nursing.

Burgess described her most notorious cases in A Killer by Design: Murderers, Mindhunters, and My Quest to Decipher the Criminal Mind (Hachette, 2021) with CSON’s Steven Matthew Constantine. Another collaboration about appealed cases will debut in 2025.

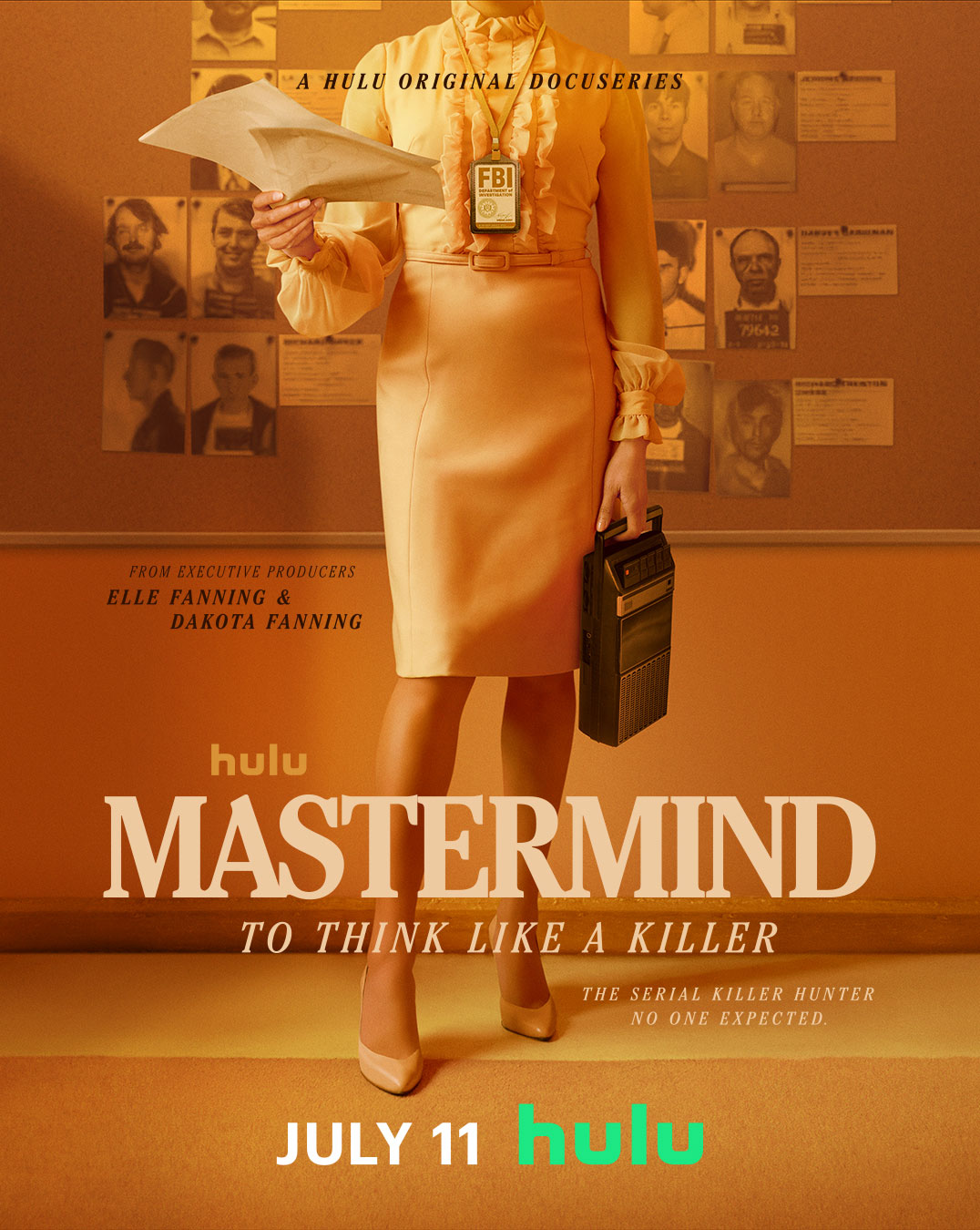

In July 2024, Hulu introduced Mastermind: To Think Like a Killer, a three-part series chronicling Burgess’s FBI profiling. She still collaborates with law enforcement, weighing in on cases such as abuse in nursing homes and the recent assassination attempt on Donald Trump.

While Burgess untangles deep inhumanity, her instincts are profoundly humane: she wants to understand what makes people, even criminals, tick. Nobody is inherently evil, she says. Instead, many criminals experience trauma without proper intervention. A grudge develops; without what she calls a “neutralization” of that grudge, anger can fester and explode into violence.

“Thoughts drive behavior. If you’re looking at someone who’s committed a horrendous behavior, you’ve got to get back inside the thought—what is prompting it, what is driving it? You have to deal with it, and try to neutralize it, so it doesn’t become a driving force within the individual,” Burgess says.

“If you’re looking at someone who’s committed a horrendous behavior, you’ve got to get back inside the thought—what is prompting it, what is driving it? You have to deal with it, and try to neutralize it, so it doesn’t become a driving force within the individual.”

—Professor Ann Burgess

In the Menendez case, for instance, Burgess testified about the brothers’ domineering, abusive father, José. Eric had hoped to go to UC Berkeley, but his father wanted him closer to home, at UCLA. When Eric realized he wouldn’t be getting away to a dorm, Burgess says, he panicked: “That was one of the turning points. He had a fear of his parents. I remember looking at this case and saying, ‘This is not a case of money. They have all the money. It’s got to be the family.’”

Burgess also lends her forensic expertise to cases closer to home. She’s enthusiastic about her work with CSON’s new Center for Police Training in Crisis Intervention, directed by Assistant Professor Victor Petreca, which studies evidence-based approaches for improving first responders’ interactions with people experiencing behavioral health issues.

Participant in Collegiate Warrior program at Boston College

In addition, she oversees the Wounded Warriors in Transition course, open to all Boston College students. Again, Burgess wants students to understand people with complicated backgrounds. Veterans visit her classroom to share intense stories about deployment. For their term paper, students interview a veteran. To their surprise, they often end up talking with a family member who hadn’t previously been forthcoming about their experience.

“I say: ‘Check your family first.’ They find people in their family who they didn’t even know had been in a war,” Burgess says. “The papers are amazing.”

FOSTERING COMPASSIONATE COMMUNICATION

“Ann has brought so much knowledge and nursing to people who have no voice,” says Associate Professor of the Practice Karen Pounds. As a psychiatric clinical nurse specialist, Pounds says she often sees stigma in mental health care, especially among people who present with complex diagnoses, have a cultural reluctance to get help, or experience language barriers.

In the case of language barriers, the relationship between patient and provider becomes essential, she says. Pounds worked at the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center, where most of her patients required an interpreter; that relational science is also a focus of her research, writing, and speaking career.

“Now, we have a greater population of patients from different countries, and we need to consider that impact,” she says.

Pounds often reminds her students that people are more than a diagnosis. “I help nurses get to the point where they’re able to see comorbidities,” she says. “Somebody can have anxiety and depression. There are people with schizophrenia who can have depression.”

She says that’s why it’s essential for nurses to see patients from a holistic perspective and to grasp their layered circumstances.

Pounds often sees stigma in mental health care, especially among people who present with complex diagnoses, have a cultural reluctance to get help, or experience language barriers.

“The essence of psych nursing is the therapeutic nurse-patient relationship: How can we develop the next generation of psych NPs with that person-to-person contact?” she says. “I came to work at Boston College because of that emphasis, and because of the values of the Jesuit education model: respecting the whole person. A lot of programs in this country focus primarily on psychopharmacology. At CSON, we’re saying to students: ‘That’s not all: you have to do psychotherapy.’”

CARING FOR THE WHOLE PERSON

Like Pounds and Burgess, Associate Professor of the Practice Julie Dunne believes in giving voice to the marginalized—including burnt-out health care providers, who may avoid seeking mental health care for fear of retribution.

As recently as 2021, medical boards in 37 U.S. states and territories asked questions that could require a doctor seeking licensure to disclose mental health treatments or conditions. And in a 2017 paper, nearly 40 percent of physicians reported being reluctant to seek mental health care because it could jeopardize their chances of obtaining or renewing their medical licenses.

During the pandemic, many providers wrestled with stress, fear, and burnout. Now, about half of Dunne’s private practice caseload comprises physicians, nurses, social workers, and nutritionists.

She has gained an appreciation for the challenges health care workers face while addressing their own mental health, and this has become a key part of her classroom teaching. “All of the students we teach at BC are going to become clinicians,” she says. “I’m excited when they ask: How do I prevent burnout and keep myself in this field? How can I make sure that I can still help people in one year, five years, and 10 years?”

Dunne teaches courses on diversity in health care as well as CSON’s graduate-level family and group psychotherapy courses. She also leads mindfulness-based cognitive therapy groups through the Harvard and Cambridge Health Alliance Center for Mindfulness & Compassion and through her own practice, Drishti Holistic Wellness.

“I’m excited when [students] ask: How do I prevent burnout and keep myself in this field? How can I make sure that I can still help people in one year, five years, and 10 years?”

—Associate Professor of the Practice Julie Dunne

She praises CSON’s emphasis on confronting social and racial injustice. Her students see psychiatric patients throughout Greater Boston, many of whom are treated in community health settings due to a lack of inpatient beds. She wants students to understand how demographics and intimate personal histories inform patients’ stories—including those of providers. And she wants them to think about how nurses can contribute to policy change.

“Students are able to see the disparities between various hospitals and funding, which invites conversation: ‘here’s how much funding goes to research around mental health as compared to physical health.’ There are many different reasons why that happens,” says Dunne. “We talk about stigma as one piece and how certain groups may be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed.”

She says she continues to appreciate Burgess’ work amplifying the experience of marginalized, often misunderstood populations.

“Her work with forensic mental health has been huge. It embodies caring for people who may not be as seen, who may be more stigmatized,” says Dunne. “Something unique about Boston College is our emphasis on taking care of the whole person. It’s not just about fixing someone’s broken leg; it’s about understanding them.”