Nobody's Fool

How Chris Hill ’90 created one of the country’s most popular financial advice podcasts.

Illustration: Michael Morgenstern

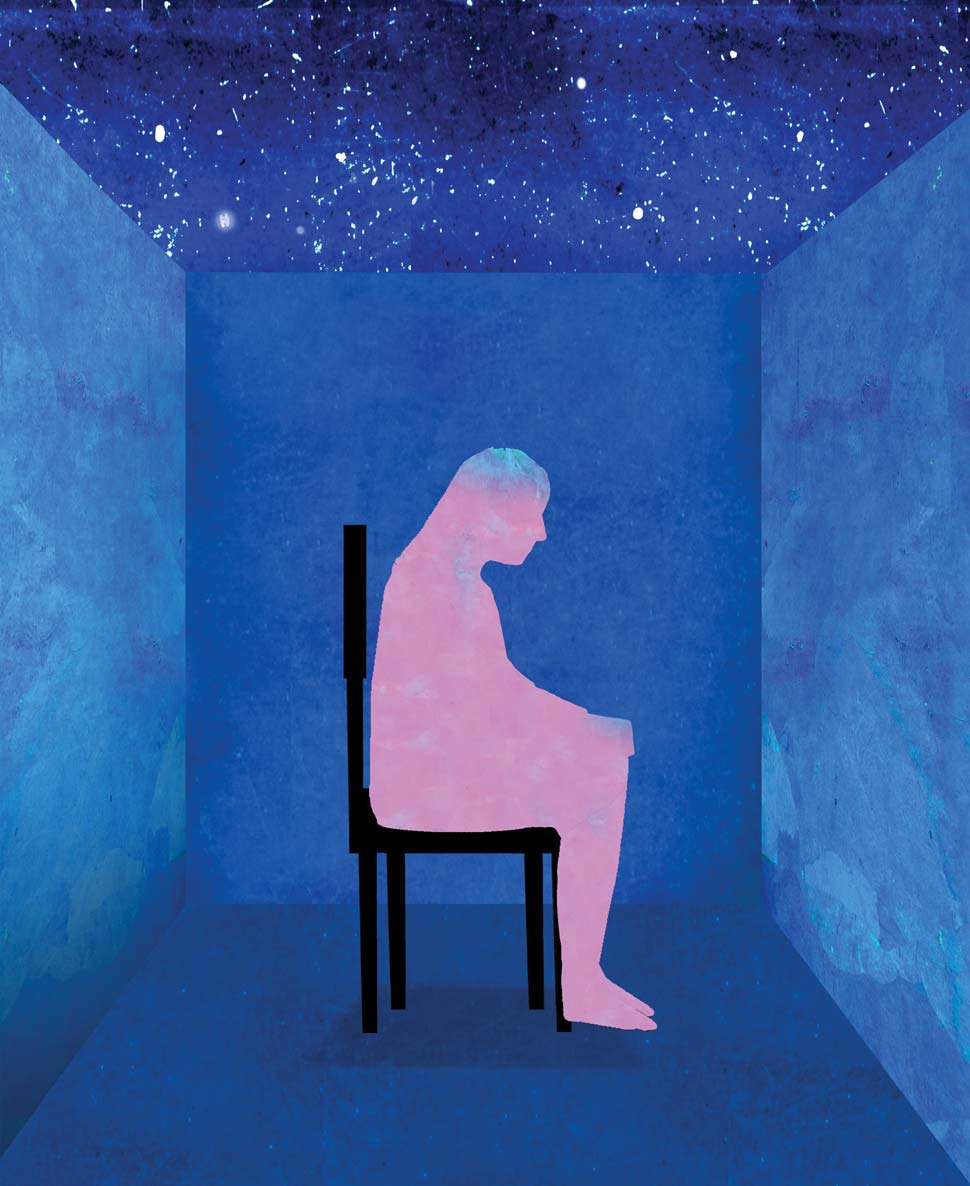

Why Are We So Lonely?

Americans are reporting alarming rates of loneliness and social isolation.

Last year, the US Surgeon General released a worrying report about the deep sense of loneliness that many Americans are experiencing. The report, “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” found that approximately 50 percent of adults in the country are feeling lonely, and that people of all ages are spending significantly less time with others.

The findings have profound implications for the health of the country. Being lonely or socially isolated puts people at heightened risk for a number of serious illnesses—the report estimates it to be the health equivalent of smoking fifteen cigarettes a day—including depression, cardiovascular disease, and dementia.

So what’s going on here? Why are we feeling this way, and how can we turn things around? To find out, we talked with Alyssa Goldman, a Boston College assistant professor of sociology whose research includes looking at how our social relationships intersect with our health and well-being. Last year, Goldman and Erin York Cornwall of Cornell University coauthored the paper “Stand by Me: Social Ties and Health in Real Time,” which explored the moment-by-moment physical and emotional benefits for older Americans of spending time with other people.

The following conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for space.

We’ve been hearing a lot lately about the societal problems of loneliness and social isolation. It turns out that these are not the same thing. How are they different?

When we’re talking about social isolation versus loneliness, we’re talking about an objective measure of someone’s social connections versus their perceptions of their social connections. So social isolation is referring to the objective lack of social ties or social connections, whereas loneliness is kind of this mismatch or perceived deficit in one’s social relationships. Loneliness is someone’s subjective assessment or evaluation of their social life. One way to think about this is that someone can have few social connections but feel very satisfied with those social ties and not feel that they’re lonely. At the same time, someone can have lots of social connections but still feel quite lonely. This kind of an “alone in the crowd” phenomenon. There are lots of indicators and studies coming out suggesting that social isolation and loneliness are problematic and pervasive in society across age groups. These are critical issues, and they’re being highlighted at a national level right now.

So you agree that we are feeling more lonely as a culture? That loneliness is more pervasive than it has been?

That’s what a big US Surgeon General’s report that came out in 2023 reported. It was based on the collection of a lot of research from sociologists and psychologists and epidemiologists, and their research is suggesting that people are reporting higher levels of loneliness.

That seems so counterintuitive in this age. We’re more connected than we’ve ever been. I can pick up my phone and FaceTime a friend. I can get on social media. Why are we feeling so lonely?

There’s a lot of research looking at the effects of the pandemic on both social isolation and loneliness, and how lockdown periods may have disrupted social ties and exacerbated feelings of loneliness that may have existed prior. Most of my research work involves studies of older adults, but there’s also a lot of attention right now on adolescents and young adults and the effects of social media on things like self-esteem and loneliness. While social media does provide us with connections, it’s more than that. There are lots of comparisons people make, and kind of this feeling of needing to keep up and of missing out.

Right, the fear of missing out—FOMO. On social media, many people are presenting a glamorized image of the amazing life they’re living. Social media can leave many of us wondering why our own lives don’t feel more fulfilling. Maybe it can leave us feeling even lonelier?

There have been suggestions that social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook are contributing to harming young people’s mental health, and that they should be treated the same way that public health treated nicotine, for example. I’m not sure about that but, certainly, there are a lot of questions about whether this is potentially damaging people by leading them to believe that their life is not as glamorous or great as everybody else’s.

Photo: Lee Pellegrini

Is there any connection between loneliness and social isolation? If someone has a group of friends and family but feels lonely, can that lead them to turn away from their contacts and become socially isolated?

There’s a lot more attention right now to how these processes play out over time. Social ties can be sources of stress and strain, but sometimes it’s not that easy to break a connection or withdraw from a social tie—family, for example, or caretaking obligations. The stress of those obligations can cause people to withdraw or pull back from the social relationships. If so, do they have other social connections? Do they form new ones? Or do they become socially isolated?

What else explains the increase in social isolation?

It could be that we are more socially isolated because, as research shows, we’re spending less time with friends, we’re spending less time with family, we’re not volunteering as much as people were decades ago. But there are also these broader demographic trends that contribute to social isolation. So for example, people are living farther from their families than they did in the past. People are having fewer children. Marriage rates are down. When we look at trends in social connections and social isolation, if we’re looking at something like How many kids do you have? How many family members do you have? then yeah, that’s declining. All of these factors contribute.

Your research also looks at the ways that major life transitions as we age can affect our social connections.

Yes, retirement, for example, is a big shift in someone’s life that can disrupt their social network. If they’re going to work every day, going to the office, seeing people, and then that isn’t there anymore, it can contribute to social isolation. Widowhood is another contributor to social isolation, especially if someone shared a lot of social ties with their deceased spouse. Sometimes the spouse who passed away was the connector, the glue in the larger circle of friends.

So you lose your network of friends in addition to your spouse.

That can happen. Health is a huge factor as well. As mobility declines, it becomes harder to do things like get together with friends, engage in activities or religious services, or volunteer.

Why did you choose to focus on later-life adults in your research?

Later life is this part of the life course where there’s so much happening. There are these transitions, like I mentioned earlier: the loss of loved ones, retirement, becoming a grandparent, changes in health. All of these changes that alter the rhythm of everyday activity and can affect social connections. You kind of see the culmination of all of these things that happened from infancy through childhood and adulthood—and to still be able to observe changes in people’s well-being at that later point in the life course is really fascinating.

You seem to be describing a situation in which our social connections can actually influence our physical health. Is that true?

Absolutely. There’s a lot of evidence that social ties can actually have as significant an effect on health as things like smoking and physical activity. And in some of my work, I’ve found that older adults who increase their social network over a five-year period have better sensory functioning. We might not initially think of sensory health as being as important as, say, cardiovascular health, but we’re talking about the ability to see and hear and smell. These are things that affect the quality of everyday life in really important ways.

Do we know why improved social connections provide these benefits?

I’m not a medical doctor, but there’s the idea that our sensory systems may have these kind of features of plasticity, and that our social life is potentially a source of stimulation and enrichment. We see this with cognition, for example. There’s this “use-it-or-lose-it” thesis that if you’re using your cognitive abilities you can maintain them. People often think of things like doing crossword puzzles. But there are also things like going out and socializing with people, maintaining a large social network, and engaging in different social activities that can also contribute to cognitive health.

“There’s a lot of attention right now on adolescents and young adults and the effects of social media on things like self-esteem and loneliness. While social media does provide us with connections, there’s also this feeling of needing to keep up.”

What were some of the highlights from the research you conducted for the 2023 paper you coauthored, “Stand by Me: Social Ties and Health in Real Time”?

This was a fun study. We used data that we gathered from older adults who were living in Chicago, but we gathered the data a little differently than other studies on social life and health. Typically, surveys of older adults are done via an interview, or by having participants write their responses on paper. And these surveys are conducted once, or maybe every year or every five years. We did all of that but then we also asked older adults to carry around a smartphone for a period of a week. And five times throughout the day, they were pinged on the phone and asked to respond to a bunch of questions about what they were doing at that very moment—who they were with, where they were, how stressed they were, how tired, how happy, how energetic. And so in this paper, we asked the question Does being with other people in a given moment affect the way that people feel in terms of their health?

And what were the results?

We found that being in the company of somebody else at a given moment leads to older adults feeling less fatigued and feeling less stressed in that given moment. This certainly mirrors a lot of findings that we already have in the literature, but the kind of contribution here is looking at this moment by moment, as opposed to asking more general questions about how socially connected someone is. This is suggesting that being socially connected is not just some kind of chronic, static thing. It’s not that we’re either socially connected all the time or we’re not socially connected at all. Being socially connected can change and unfold in what we call real time, or on a momentary basis.

It sounds like we may actually draw energy from being around people. Presumably people we like?

That’s a good question. We don’t know if these are people they like but we did find that these effects are especially strong when older adults report being with a friend or with a neighbor. They’re more likely to engage in recreational activities like socializing, going out to eat, doing something fun together. Whereas with family, older adults are more likely to do things like grocery shopping, going to appointments, things like that.

Did anything you found surprise you?

One surprise was that we didn’t see significant differences in how often people are with others based on their network size. So, someone who says they only have one close social tie in their network was just as likely to be with somebody during the day as someone who reported that they had five very close social ties. This really drives home that our social lives are dynamic and fluid, and to understand the effects on health, we have to look at these different levels and layers.

Are there things we can do as a society to promote and facilitate these beneficial social connections?

There’s been a lot of attention lately to the broader social environment—so not just someone’s interpersonal connections, but the social infrastructure of where they live. So things like libraries, parks, senior centers, and other community spaces that are conducive to supporting the formation and maintenance of social ties. In fact, after our paper was published, we heard from Middlesex (Massachusetts) District Attorney Marian Ryan’s office. It was really interesting to hear about this program she’s doing throughout Middlesex County called the “Let’s Connect Initiative.” Part of the project is placing benches in certain areas, the idea being that the benches will kind of facilitate conversation and connection across generations. Then, in the Netherlands, there’s apparently a grocery store chain with a checkout line for people who want to chitchat with the cashier for a little bit. Time will tell if these kinds of initiatives have lasting effects in our increasingly socially isolated and lonely society. In chatting with a cashier at a grocery store, does somebody feel less lonely in the moment? Possibly. Does it build a lasting social connection that can be a reliable source of social support? I’m not sure. But our work does suggest that these momentary things still matter for well-being even if it’s a fleeting, momentary interaction. And when we think of health outcomes and premature mortality, our society typically focuses on things like changing someone’s physical activity or diet or prescribing a medication. I think social ties have been absent from that conversation. So it’s really exciting and important to start seeing more attention being seriously given to social connections.

You also have an NIH grant that’s looking at social connections and cognition.

It’s looking at interpersonal ties and close social networks but then also looking at the broader social environment. So aspects of the built environment, social infrastructure, socioeconomic measures of neighborhoods and surrounding areas, and thinking about how those factors shape cognitive function, cognitive decline, and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

And social isolation is a contributor, we think?

Yes, it is. But it’s not just the presence or absence of social ties. That is important—someone who’s socially isolated is at higher risk of cognitive decline—but it’s also the question of what about the social networks that people do have can be protective against cognitive decline?

And what have we learned about protecting ourselves against cognitive decline? Have we identified any defenses in our social networks?

I think that’s the big question that’s hopefully going to come out of a lot of the research that’s being done in this area. When somebody is sixty-five or seventy-five, can there be some sort of intervention, or is there something that can be done at that point to slow cognitive decline?

And what about our social network’s ability to positively affect our physical health?

Our social connections can be sources of stress, and it’s well established that stress can negatively affect health. But having supportive social ties can also buffer the effects of stress on health. So if you have a stressful experience in your life, a really supportive set of social ties to call on can maybe dampen the harm that event would’ve otherwise caused. We also find that social ties can be really important in the way people manage their health and well-being, like taking medication, getting to appointments, and adhering to a prescribed health regimen.

And if someone doesn’t have a robust social network?

Someone who’s socially isolated, or who lives alone, can be at much higher risk of not managing their health in those ways.

And if someone is feeling very lonely?

Loneliness itself can be a source of stress. Feeling lonely and being socially isolated can lead someone to engage in harmful health behaviors, such as smoking, or not engage in health-enhancing behaviors, like exercise. These effects can be exacerbated when someone who is lonely withdraws from social ties, and therefore does not receive support and resources that they otherwise might. Loneliness and social isolation can also activate the body’s stress response and related biological processes, which are implicated in various disease processes, and can manifest in blood pressure, immune function, and various markers for cardiovascular risk and other health risk factors. So there are various pathways through which our social relationships affect our health in significant ways, including physiological, psychological, and behavioral, in addition to being critical social resources and sources of influence that collectively shape our well-being.