Decrypting ICOs

Just what is an initial coin offering, anyway?

The 1650 work Saint Francis Xavier Before the Map of His Missions, by the Dutch artist Cornelis Bloemaert.

The Indipetae

Many early Jesuits petitioned to seek missionary glory in “the Indies.” Not all got their wish, and some, like Ignazio Maria Romeo, a schoolteacher in Palermo, spent a lifetime campaigning for the call.

On April 26, 1703, a Jesuit in his twenties, recently recovered from an illness, wrote from Palermo, Sicily, to Tirso González de Santalla, SJ, the Jesuit superior general in Rome: “The [Indies] mission is putting the quill in my hands. I’ve asked it of Your Reverence several times already . . . [and] I feel obliged to expose to Your Paternity once again the petition for my longed-for Indies, . . . heart, mind, and quill. It was only for this reason that I miraculously regained my corporal forces and health, because all the physicians were talking about my death as imminent. . . . If I do not devote my life to the missions, I fear I will die soon.”

Written on handmade paper in purple-black or brown-black ink that is now faded to dark brown, the one-page letter was sent by Ignazio Maria Romeo, SJ (1676–1724?), the eldest son in a significant Sicilian family. Fifteen such letters from him are preserved in the central Jesuit archives in Rome—another fifteen that he is known to have written are lost—while letters and documents concerning his life in the Society can be found in other archives.

Romeo’s letters are themselves part of a collection of more than fifteen thousand “Indies” petitions that were written by Jesuits between the 1560s, when the Society of Jesus was still new, and 1773, when the Society, by then twenty-three thousand priests and brothers, was suppressed by Pope Clement XIV and its members dispersed. The letters are known as indipetae, a contraction of litterae Indiam petentes, or “written petitions for the Indies”—Indies in this case being an all-purpose term referring to areas of the world where Christianity had never rooted: principally North and South America, India, Japan, and China.

Usually no more than a few pages long, and following a formula that included a brief essay on why the writer wanted the assignment, many of these indipetae were perfunctory in tone, as though the authors were simply discharging an obligation. In other cases, however, and certainly in the case of Romeo, the petitions—some of which included passages written in the petitioner’s blood—reflected a passion to escape a Europe-bound career of ministry and teaching and embark on a life of glory and sacrifice (even martyrdom) while bringing the faith to pagans.

Those Jesuits who sincerely yearned for a life in the Indies looked to the example of legendary missionaries such as Francis Xavier, the “Apostle of the Indies,” whose feast day, December 3, was often the dateline on their petitions, or Matteo Ricci, who in 1601 made his way into the Forbidden City of Beijing. The indipeti, as writers of these petitions were called, were also inspired by published Jesuit accounts of mission life in far-off and exotic places. These reports were sent by missionaries to Jesuit headquarters in Rome, where they were expurgated and embellished; many becoming “bestsellers” read by both lay and religious men and women.

Among the popular accounts of life in the Indies were the Litterae annuae, collections of Jesuit reports that first appeared in 1583, five decades after the order was founded. Later, vernacular versions were added, including, for French consumption, the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses des missions étrangères par quelques missionnaires de la Compagnie de Jésus (Enlightening and curious letters from foreign missions by some missionaries of the Society of Jesus), and Neue Welt Botte (The New World Messenger), published for German readers in 1726. Also popular throughout Europe were romantic hagiographies that members of the Society produced to celebrate their saints, including missionaries to foreign lands.

The men of Romeo’s generation who petitioned for assignment to the Indies were usually products of Jesuit primary schools—which were of high quality and free—who went on to join the Society in their mid-teens, spent a decade or more receiving further education and training, and were ordained in their late twenties or early thirties. Their first assignment was likely to be teaching and ministry in Europe or overseas. As many young writers of indipetae, including Romeo, explicitly wrote, the missions to the Indies appealed to their desire for novelty and adventure—strange peoples, fauna, landscapes, languages. The Indies also connoted danger and martyrdom, and many intimated in their letters that they yearned to live out Christ’s sacrifice, saving other souls while saving their own.

The letter by Ignazio Maria Romeo quoted above was the third petition to the Indies that he sent to the superior general of the Jesuit order. (He would ultimately communicate with two such men: González and his successor in 1706, Michelangelo Tamburini.) Romeo’s first petition, which has not survived, was sent in 1701, and the second in January 1702, when Romeo was teaching grammar and humanities at the College of Palermo and ministering locally. The son of a Sicilian nobleman who was a financial supporter of the Society, Romeo had every expectation that he would be granted his wish to be sent abroad, and in January 1704 he did in fact receive license to go to the Americas.

In his late twenties at the time, he wrote to González with his thanks, signing himself “the Happiest Indian” and declaring “I see myself closer to Paradise the farther I am from Palermo.” But Romeo’s delight was belied by several paragraphs in which he complained that his local Jesuit supervisor had asked him to put off his departure for some four months, until after Easter.

“[I] would be calmer,” Romeo wrote the general, “if Your Reverence would order a more immediate departure for me, because I would not want to incur, because of the delay, some impediment.” He must have realized that his parents, like many fathers and mothers in similar circumstances, were anxious to keep him near home, and that because of their standing as members of the Sicilian nobility—Romeo’s father was a marquis—they had the power to influence even the superior general, with whom his father was acquainted. He continued, naively as it turned out, “I no longer fear disagreements with the Marquis, my Father, because . . . he decided to agree to the divine plans. Indeed, to better conform himself to them, he is making the Spiritual Exercises in this Professed House where I am as well.” He concluded in a postscript, “I beg you to call me as soon as possible to the ship.”

It was not unusual for Jesuit provincials or parents to try to block the missionary aspirations of their charges and sons. Provincials didn’t want to lose able and useful men, and parents were well aware that a departure for the Indies meant they would never see their son again. But Romeo had more reason to worry than he knew. Six weeks after he sent his letter of thanks and concern, his father sent this letter to General González in Rome:

Palermo, 4 March 1704

Ignazio Romeo Marquis dei Magnisi to

Tirso González de Santalla, SJ

My son, Father Ignazio Maria Romeo, visited us at home with the objective of wishing farewell [before] leaving for the Indies, where he says that God is calling him. This news came completely as a surprise, also for the Marchioness, my wife and [Ignazio’s] mother, and I saw her totally oppressed by the pain. . . . Even if she did have some knowledge of his vocation, this news was so unexpected, and the departure so sudden, that she became overwhelmed by an intolerable grief, crying as if [Ignazio] was about to die.

I went to the Provincial asking for help, promising that I would not leave until he granted me permission to speak to you. . . . I will give you sincere and truthful information about the state of my house. God wanted me to be the father of 20 children, but he has called to Himself half of them. . . . Ten are alive: The first-born is Father Ignatius (the second is already married). . . . The other eight are young, three are spinsters, . . . the eldest is not yet 14, and the last two are not yet weaned.

I am 48 years old. I have neither father nor mother, nor brothers nor sisters. The same is true for the marchioness, who is 44 years old, in poor health and devastated by 20 deliveries in addition to the many miscarriages she suffered (often one or two) between one childbirth and another; she suffers a condition founded in hypochondria that causes her on occasion almost to go out of her mind.

[In] these circumstances we [cannot be] deprived of the only child from whom we may gain some benefit, if for nothing else, at least to assist in closing our eyes . . . . I think it would be more appropriate, instead of sending him . . . to be a martyr, to give him to his father and mother, because divine and human laws prescribe every assistance from sons and daughters.

My wife’s health is worsening. She is becoming more and more attached to her children, even in the case of the ones who died, more than is appropriate. . . . Even according to the physicians, [if Ignazio left] either she would go completely mad or she would die of an apoplectic fit, and so I would be without both son and wife. . . . All these reasons must, in my opinion, be taken into consideration.”

The marquis was not the only person endeavoring to block Romeo’s ambitions. At about the same time this letter was sent, Romeo received a communication from Rome informing him that his departure for the Indies had been postponed “for his mother’s sake.” He was furious, writing to González that he thought the Society of Jesus should “easily see past my mother’s tearful assaults.” As regards his father, he wrote, “[For him] to hope for help from me is a chimera. I will help his house only with my prayers.” He concluded, “I see that the path to my longed-for Indies is almost entirely precluded to me.”

González had the difficult responsibility of replying to the Marquis and to Romeo—both of whom were important to him and to the Society. He told the Marquis that “we are not forgetting the owed consideration towards your person and your wife in deciding about the departure of your son.” And in a parallel letter, he praised Romeo for his “holy estrangement” from his parents, at the same time suggesting that he try to make peace with them. Romeo responded that it was impossible for him “to find the Indies in Sicily, I’m waiting for the Real Indies.” He did, however, note, “I remain silent and direct all possible energy toward calming my relatives . . . [who] seem more stubborn than ever.” He added that he would “renew every year my requests until I receive the Indies.”

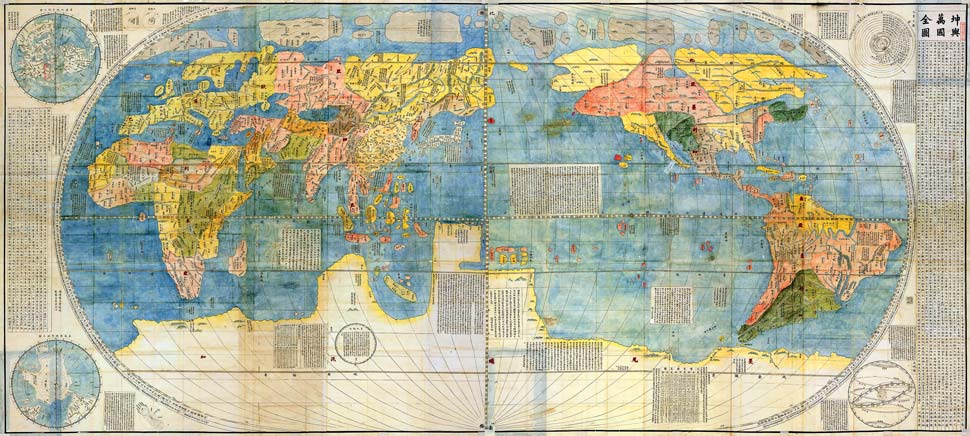

An unattributed version of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu world map created in 1602 by the influential Jesuit author, theologian, and cartographer Matteo Ricci. Image: Wikimedia Commons

As noted above, Romeo would send more than thirty petitions to Rome over the course of nearly two decades. In return, he received praise for his work in Sicily, mild encouragement with regard to the Indies, and instructions to be patient. According to archival evidence, over these years he became a productive and valued member of the Jesuit community in Palermo. In 1711, the order’s new general, Michelangelo Tamburini, recognizing what likely all but Romeo could see, finally foreclosed on an Indies mission, writing “your age [35] is very advanced [and] you would experience many complications in learning a new language, not only foreign but difficult. [The] time you would spend in the long journey, the things that you would leave undone in Sicily, where you are such a good worker for God’s sake—everything makes it not only hard, but impossible to fulfill your desires.” The general counseled him “to content yourself [with work in Palermo], to exercise your zeal for the benefit of Souls, and believe that the Lord wants nothing further from you.”

But Romeo could not accept this counsel. His further letters to Tamburini are lost, but Tamburini’s gentle remonstrances have been preserved. The instruction in a letter dated August 1713 is typical: “Enlist your apostolic fervor for the missions in these our parts. While your desire for the more distant missions of the Indies will itself attract a reward.”

Romeo seems to have written the last of his indipetae petitions late in 1717, when he was in his early forties. “In no other place as much as in this very kingdom may be found those Indies to which you aspire,” Tamburini responded. “Attend to sanctifying these people with untiring zeal, and in time you will receive from the eternal Remunerator that same crown which others will win through their hardships among the barbarians of Asia and America.”

Five years later, in October 1722, Romeo wrote to Tamburini to ask permission to leave the Society of Jesus and enter another religious order. Pointedly, he noted that he’d been contemplating such a change for twenty years, which would date his considerations to his earliest years in the Society, when he first had expectations of an exotic assignment and concerns his wish would not be granted.

In response and over the next two years, Tamburini, again gently and in paternal tones, tried to persuade Romeo to change his mind. Again he praised Romeo’s domestic work and “zeal” and expressed admiration for the “satisfaction” Romeo had always taken in obeying orders. Tamburini—who clearly did not want to lose Romeo as a Jesuit—wondered in his letters if illness was the cause of his determination to break away. He asked Romeo if he considered the shame he’d bring upon himself, the Society, and his family if he left. Within the Society of Jesus, the superior general reminded him, Romeo could find a “very large field of endeavor, . . . probably larger than in any other [religious order].” In April of 1723, Tamburini ended a letter, “I love you from the bottom of my heart! I love your true goodness—spiritual and temporal—and your reputation. I pray God to enlighten you.”

In July of that year, eight months after the correspondence about Romeo’s exit from the Society began, Tamburini wrote “to grant to the Provincial Father all the necessary authority to allow you the hoped-for passage to another [order].”

Whether Romeo in fact left the Society is not known. If he did leave—there are indications he was considering the Capuchins and Franciscans—he did not do so immediately. His remonstrations with Tamburini continued in letters for another seven months, with the Jesuit general still holding out hope of Romeo’s “repentance.” At one point, Romeo asked for permission to plead his case directly to Tamburini in Rome. But the general responded that at Romeo’s age—he would have been in his mid-forties—the journey would be too perilous.

The Jesuits have always kept precise records, and if Romeo left the Society in 1724 or thereabouts, as may be the case, his name should have appeared on an annual list of dimissi—those who’ve been removed from the order. But it does not. Nor does it appear on contemporaneous lists of defuncti—the dead. In 1724, Ignazio Maria Romeo, SJ, simply disappears from Jesuit records.

The Society’s archives are voluminous and in many cases not deeply explored, and it is possible that somewhere within them is a record of Romeo’s final days as a Jesuit. Such a record, whatever story it may eventually tell, is unlikely to offer more to the understanding of Jesuit history in the first quarter of the eighteenth century than do Romeo’s poignant indipetae and associated documents. They illuminate a minor, perhaps commonplace, life in the Society, and an aspect of Jesuit culture at a particular moment in time, with intimacy and personal resonance that few other known collections of Jesuit documents offer.

In his last years, however they were spent, Ignazio Maria Romeo may have thought of himself as a man who failed to live out the mission for which he was made. But in considering his gift to Jesuit history, it’s difficult not to recall Superior General Tamburini’s comforting supposition that, over the years of his frustration in Palermo, Romeo may have earned “as great a crown” as “others will win through their hardships among the barbarians of Asia and America.”◽

Elisa Frei, an Italian scholar, was a research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies at Boston College during the 2017–2018 academic year. She is currently writing a book on the indipetae and editing an edition of an Italian treatise on the early experiences of the Society of Jesus in the Far East.