Listen to clips of interviews, read quotes, and view images and documents collected as part of the GAA Oral History Project Archive.

View and listen to a selection of images, interviews and other material relating to a specific county.

A league playoff match between University of Ulster and Queen's University Belfast in 1988. ©Cumann Camógaíochta na nGael

Located in the north east corner of Ireland, Antrim is regarded as a stronghold of Ulster hurling. Gaelic games and, in particular, early forms of hurling were played in the county throughout the nineteenth century. The game, as designed by the GAA, eventually took hold in Antrim at the turn of the twentieth century following frequent visits by Michael Cusack to Belfast coupled with the establishment of the annual Feis na nGleann. A tradition in the game established, Antrim would develop into a powerhouse of Ulster hurling throughout the twentieth century. Football, by contrast, endured a more chequered experience. Despite a period of progress in the 1940s, the onset of the Troubles in the 1970s had a devastating effect on football in the county, precipitating its decline. Even so, Antrim teams have been recognised for their contribution to the game and the St John’s club of west Belfast was central to the establishment of the All-Ireland Club Championship. Their near neighbours, St. Gall’s, are the most recent Antrim team to win the All-Ireland Club Football Championship, doing so in 2010, while fellow Antrim club Loughgiel Shamrocks won their second All-Ireland Club hurling title in 2012.

An invitation by McQuillan G.A.C. to a victory celebration in 1953. The price of admission for ladies was cake. ©McQuillan G.A.C.

Gerry Barry, b. 1940

Gerry discusses the origins of Casement Park and the reasons for its construction.

Gilly McIlhatton, b. 1931

Gilly describes how all GAA clubs in Belfast are located on the Falls Road.

'Believe it or believe it not, I got a Protestant fellah out to play for Agohill. Me and him ran up the hill on the bikes from Agohill – I was born and reared in the village – football boots over the handlebars of the bike, the green and white jerseys stuck inside the coat. My mother kept the two jerseys. He couldn't take a green and white jersey down to the house; his father was an Orangeman. And he was a good player. I had an eye for a good footballer then, even at school. He was a great footballer. His father got to hear about it and stopped him playing and that fellah went on to be a Northern Ireland schoolboy international.'

- John McGuigan, b. 1941

© GAA Oral History Project

'The first time I ever played pulled a shirt on for Brackenstown was in Davitt Park and I played outside left; Leo Mallen played outside right. We didn't even have football boots. We were dressed out in the kit and football socks but we had nothing only whatever we wore in those days and it probably wasn't shoes, it was boots. I don't think I ever touched the ball that night but it was great to run out on Davitt Park, which was our Croke Park of the day.'

- Willie Grogan, b. 1939

© GAA Oral History Project

'I remember when I was 14 playing a hurling match on the Glen Road in west Belfast, it was 1976, the height of the Troubles. Frank Stagg had died on hunger strike in jail in England, there was serious trouble on the streets of nationalist parts of Belfast. A gun battle broke out nearby where we were playing and bullets were literally whizzing past our heads. Both teams had to hit the deck and crawl off commando style, using our hurls like rifles! We thought it was great craic, think the match was declared a draw! But for the GAA in west Belfast, many more young lads could have been drawn into the conflict. Challenging times indeed and a huge debt of gratitude is due to all who gave their time.'

- Paul Collins, b. 1962

© GAA Oral History Project

A high ball is contested in a minor match between Armagh and Cavan in 1951. ©Cardinal Ó Fiaich Memorial Library

For all its present profile as a football stronghold, success was late in coming to Armagh. Between 1903 and 1950 the county did not manage to win a single Provincial title, losing in twelve Ulster senior football finals. As in other counties north of the border, the outbreak of the Troubles had a direct effect on the playing of GAA games in the province. The occupation of Crossmaglen Rangers' grounds by the British Army in the 1970s served as a physical symbol of how the conflict in Northern Ireland affected the GAA. It was this very club, however, that led the reinvigoration of the game in Armagh. Crossmaglen Rangers’ dominance at both county and All-Ireland level in the late 1990s and through the early 2000s has earned it a reputation as one of the most pre-eminent Gaelic football clubs in the country. Crossmaglen’s success in turn aided the resurgence of the county team and in recent years Armagh football has enjoyed a great deal of success. The evidence for this is can be seen in Armagh’s remarkable run of success at the turn of the Millennium, winning seven Ulster championship titles between 1999 and 2008, and a long awaited All-Ireland title in 2002.

A membership card for Armagh Harps GFC from 1957. ©GAA Oral History Project

Marian McStay, b. 1940

Marian discusses the relationship between the GAA and the different religious communities in Armagh.

Joe Sherry, b. 1927

Joe recalls competing in sports days in his early years.

'The beauty to me of Gaelic football is that you go to watch Armagh playing in Croke Park and there's 82,000 people there and every one of the 82,000 people knows someone who's playing. They don't live that far from you. You'll know somebody who's playing on your team that you're there to support.'

- Mary Keegan, b. 1955

© GAA Oral History Project

My biggest day was not winning the All-Ireland. My biggest day was the year we won the first Ulster Championship because we had won nothing for about 15 years. We had won nothing since 1978 and that was really the thing to me that we're on the right track.'

- Peadar Murray, b. 1947

© GAA Oral History Project

'I would say to any family [to] put their youth into clubs; football clubs, hurling clubs, handball clubs, camogie clubs. You will never go far wrong with friendship, comradeship and being looked after and brought places you might never get to. For people who want to help their association and to help their locality. And that's the way I see it.'

- Jimmy Carlisle, b. 1931

© GAA Oral History Project

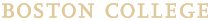

The six Morrissey brothers from Ballycrinnegan, St Mullins. Mick is the only native of Carlow to have won an All Ireland hurling medal, doing so with Wexford. ©GAA Oral History Project

The organisation of Gaelic games in Carlow was preceded by that of a number of other sports: the Carlow Cricket Club, the Carlow Rugby Club and the Carlow Polo Club were, for example, all born before the GAA in the county. The GAA in Carlow held its first county convention in October 1888 and its slow pace of development continued across the early decades of the twentieth century. The county’s problems mounted with the loss of their strongest club, Graiguecullen, who, after being absorbed into Carlow from Laois in 1904, returned to that neighbouring county after a row erupted in the mid-1920s. Despite this, remarkably, Carlow football went from strength to strength during the 1930s with the early 1940s constituting the county’s most successful era, when they contested three Leinster football finals in four years. After losing to Dublin in 1941 and 1942, the Barrowsiders overcame the same opposition to win their first, and so far only, Leinster title in 1944. Hurling developed at a slower rate than football in Carlow, being most popular in the south of the county, close to the hurling strongholds of Wexford and Kilkenny. That being said, the county’s senior hurling team have twice won the Christy Ring cup and its minors reached a provincial final in 2006.

A letter from the Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Spellman, granting Kildavin GAA permission to call their new grounds after him. ©GAA Oral History Project

Brendan Hayden, b. 1936

Brendan talks about the different types of training he undertook for the county team and the facilities available.

Micheál Jones, 1920

Micheál recalls the formation of St Andrews GAA club in Bagenelstown and the rivalry that existed in the town before the club was formed.

'The 1944 Leinster Final when Carlow defeated Dublin in Athy, I travelled from the Curragh camp in Kildare to see it. They were my heroes. I was sent a photo of the team recently and re-lived their faces only to be told that they were all dead now, a reminder of our mortality.'

- Patrick Somers, b. 1923

© GAA Oral History Project

'We've Rathnure just up there and we have Kilkenny on the other side and that would've influenced the hurling. What amazes me – I'm a blow in obviously – what amazes me is that we in St. Mullins have held out players that are on the border; that are in the parish but would be living in Co. Wexford and we've held them.'

- Úna Murphy, b. 1956

© GAA Oral History Project

'The 'scallion-eaters' were Carlow…It was very fertile land – Carlow would be very famous for it and the vegetables and all that would be top quality. In '44 back again to Jimmy Travers, they went by donkey and car and they had scallions in the thing you put over the donkey's ears...They'd have scallions all around them, you know heading down the road. They drove the donkey to Croke Park, 52 miles. It could take them nearly a whole day.'

- Vinny Harvey, 1937

© GAA Oral History Project

Local club members working hard to level ditches for Cornafean's new grounds in 1961. ©George Cartwright

Cavan hold more Ulster senior football titles than any other county in the province. Following a brief decline at the end of the nineteenth century, the GAA in Cavan was revived at the beginning of the twentieth century and it was not long before the county became a powerhouse of Gaelic football, winning a plethora of Ulster titles between the 1920s and 1940s. This was the heyday of the sport in Cavan; All-Ireland successes were achieved in 1933, 1935, 1947, 1948 and again in 1952. The standout victory among all these was arguably that of 1947, when Cavan defeated Kerry in a final played in the New York Polo Grounds. The sporting fortunes of the county ebbed in the second half of the twentieth century with only a single Provincial title – in 1997 – being added after 1969. Nevertheless, the contribution of Cavan to the emergence and development of the GAA in Ulster is a singular one: it was here that the GAA first expanded into Ulster with the Ballyconnell Joe Biggars club – named after a Nationalist MP - being the first to affiliate to the Association in March 1886.

Training tips given by Cavan County Secretary Hugie Smith to players at a training session in 1952. ©GAA Oral History Project

Tony Connelly, b. 1941

Tony discusses the history of Ballyconnell First Ulsters and the controversy surrounding the club's claim of being the first GAA club in Ulster.

Cavan Gaels GAA

Members of Cavan Gaels GAA sing an old club song.

'Daddy only went to watch the boys play. For some reason or another he just didn't think girls should be playing sport. But in the end, as things went along, I ended up winning more than the boys and he started coming around to the idea, when he started seeing the trophy cabinet with more girls' trophies than boys' trophies he said there must be something in this ladies' sport. And it was only then that he started taking an interest.'

- Rosie O'Reilly, b. 1969

© GAA Oral History Project

'The G.A.A. has changed in many ways. It now has to compete with a huge number of other sports. Not only were we not allowed to play 'foreign games' we could not even watch them. Thankfully the 'ban' as it was called is gone and the games have to compete on their own merits.'

- Jim McDonnell, 1935

© GAA Oral History Project

'Most communities are completely run by football, it's what you do at the weekend, and if you go out, it's what you talk about, and it's great when it can bring people together in that kind of a way.'

- Mark Farrelly, b. 1990

© GAA Oral History Project

Ladies tog out for the Parteen Camogie team in the church grounds in Shannon c.1980s. ©Dόnal Ó Riain

Birthplace of the founder of the GAA, Michael Cusack, Clare was one of the early converts to Gaelic games. In determining how the games developed, however, geography has played a major role, with football predominating in the west of the county and the hurling in the east. As in many counties, participation in the GAA fell in the latter stages of the nineteenth century as a result of socio-economic hardship and political strife. Clare’s double All-Ireland senior and junior hurling championships in 1914 signalled a revitalisation of the GAA in the county and notwithstanding splits in the local organisation during the Civil War, a strong club and schools structure was developed in the decades following independence. Nonetheless, it was not until 1992 that Clare could celebrate a Munster football final triumph over Kerry. Success for the hurlers followed soon after when in 1995 they won the county’s first All-Ireland title since 1914, an achievement repeated in 1997.

An invite from Guinness to attend the All-Ireland Hurling Championship Quiz Final in Guinness Storehouse. ©John Maher

Jack Dunleavy, b. 1910

Jack recalls the local parish team known as the Shamrocks, who played on an old cricket pitch.

Mick Leahy, b. 1925

Mick describes how when he was younger hurls were hard to find so they used makeshift ones known as 'spocks'.

'It did not affect my family life much when I was single, however when I got married my wife had to endure many evenings on her own while matches and training were taking place. I travelled home early from a family holiday in Portugal to play in a county final for my club. My wife stayed in Portugal, to finish the holiday.'

- Gerard McNamara, b. 1952

©GAA Oral History Project

'Short of taking the hurley to bed with me it was virtually in my hand from the time I got up till I went to bed. I was so proud to be representing my family and relations, particularly my father R.I.P who devoted almost all his spare time to supporting the game. As it stands today I believe it to be more 'Big business' unfortunately which has somewhat taken away from the pride in the parish and team and team mates, and I don't see how that element of the organisation can be restored.'

- Seán McInerney, b. 1960

©GAA Oral History Project

'My father told me he made his own football boots as he was a shoemaker and they were the envy of all. He gave one boot to my uncle John Joe for one game and he wore the other, resource sharing in its earlier form.'

- Brian Galvin, 1960

©GAA Oral History Project

A match at Sam Maguire Park in Bantry in 1960. This was the last match that excursion trains ran to Bantry as the West Cork railway closed down in 1961. © GAA Oral History Project

One of the most successful dual counties in the country, Cork have built an enviable reputation in All-Ireland competitions in both codes and at all levels. The largest county in Ireland, the playing of hurling or football in the county was often geographically determined. Traditionally in Cork, an urban and rural divide has existed with urban clubs dominating the hurling scene while rural clubs historically fared better in football. This has changed over time, however, with Nemo Rangers from Douglas ending the dominance of rural teams on the local football scene and progressing to win the All-Ireland club football title on seven occasions between 1973 and 2003. The strength of the GAA in the Cork is reflected in the profile and status of many of its leading personalities, with Christy Ring from the Glen Rovers club, winner of eight All-Ireland hurling titles in the mid-twentieth century, the most exalted of the lot. Corkmen have also given their names to the most prized trophies in Gaelic games, the Sam Maguire cup being awarded to the All-Ireland football champions with the Liam McCarthy cup presented to the victorious All-Ireland winning hurling team.

An entry in Midleton GAA's minute book dated 19th October, 1902. At this meeting a decision was made to amalgamate two pre-existing clubs in to one. © GAA Oral History Project

Tom Daly, b. 1937

Tom describes how his father and uncle made hurls and talks about the different steps in the building process.

David O'Brien, b. 1923

David recalls how Jack Lynch gave his Glen Rovers team a pep talk at half time during a championship final in the 1960s.

'Money was very scarce when I was young so we had to save up to travel to matches. During the winter I snared rabbits, got up early to take rabbits out of snare and sold them in Midleton. Early summer, I thinned beet and late summer I picked 'wild' mushroom in the fields and bogs and sold them to passing motorists on the main road. Out of all of this I was able to travel to two games by train from Midleton Railway Station.'

- Ted Murphy, b. 1943

© GAA Oral History Project

'The field across the road from my home was known as 'the Hurling Field' and used daily from March to October for hurling practice and matches, fewer matches than nowdays, boys and men came to the 'Field' every evening to pick around a dream! They walked, ran, very few had bicycles, and always tried to get to the 'Hurling Field'. It was the main 'social meeting' place.'

- Eileen M. Carr, b. 1929

© GAA Oral History Project

'The GAA leads the way in terms of doing everything because when you go down to rural Ireland the one common thread is that every parish in Ireland has a GAA club. The ESB is the only other organisation...that goes into every parish in Ireland...it has so much in common with the GAA - they both are so rooted in the real Ireland.'

- Derry O'Donovan, b. 1945

© GAA Oral History Project

A high ball is contested during a match in Ballinascreen. ©GAA Oral History Project

The story of the GAA in Derry is twofold: the city and the county. The failure to establish itself with the same level of organisation as in other counties meant that the expansion of the GAA in Derry was slow with periods during the early twentieth century where the playing of both football and hurling was, at best, sporadic. The mid- twentieth century saw the expansion and development of the GAA in rural parts of Derry but it also bore witness to the near collapse of the Association in the city, where soccer provided stiff competition. Significant advances were made in the city following the opening of Celtic Park GAA grounds in 1943, but many of the new clubs that sprung up soon disappeared. It is only in recent times that the GAA has made progress in the city. As in many counties, the intertwining of the GAA and politics was clearly visible within the nationalist movement in from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to the more recent Troubles, which erupted in the 1970s. The ongoing strength of the GAA in rural areas was manifest in the All-Ireland club success of Lavey in 1991. And this club success soon translated onto the inter-county stage when in 1993, amid scenes of great jubilation, Derry won their first All-Ireland football title.

A membership card from Owen Roe GFC from c.1950s ©GAA Oral History Project

Foncey O'Kane, b. 1942

Foncey discusses the history of O'Brien's Foreglen GAA Club and how there is evidence of Gaelic games being played in the area before the formation of the GAA.

Maura McCloy, b. 1960

Maura from Ballinascreen recalls her earliest memories of the GAA and how people used to gather around the radio to listen to the All-Ireland.

'I used to travel across town to play hurling on a Saturday morning... I even remember the price of the bus; my father used to give me a pound on a Saturday morning, which was a fortune then, and 50p for the bus over and 50p for the bus back... In 1981 walking across Craigavon Bridge in Derry with a sportsbag and a hurl looked a bit strange. It was certainly a bit strange to the British Army checkpoint on the bridge at the time.'

- Paul Simpson, b. 1968

©GAA Oral History Project

'I left home at 5.30 on a Saturday evening on my bicycle and went to Magherfelt which is five miles away with my football boots tied on the bar… I took the bus to Derry and then transferred from the bus to a train to Letterkenny. I stayed the night in Letterkenny. I got a cup of tea after the match and raced to get the train… That was my experience of my first senior match.'

- Roddy Gribbin, b. 1924

©GAA Oral History Project

'We travelled by car to matches, one day 11 players travelled in the one car. The driver became distracted with the noise in the car and looked behind him and ended up in the ditch. Luckily no one was injured and we went on to win the match.'

- Frank Walls, b. 1960

©GAA Oral History Project

The view of Tawny Bay from the Kilcar GAA club pitch. ©Fred Reilly

Evidence exists that suggests an early form of hurling, known as camán, was played in Donegal from as early as the fifteenth century. With the establishment of the GAA in 1884, many counties discarded their local games in favour of those governed by GAA rules. In Donegal, however, camán continued to be played into the early twentieth century. The failure of the GAA to establish itself in its early years in Donegal was due to a number of factors outside of the association’s control. As was the case in most counties along the western seaboard, poverty and emigration were rife. These conditions, coupled with the popularity of soccer in the county, added to the slow development of the GAA in Donegal. The early twentieth century brought an improvement; the number of clubs grew and the county reached the All-Ireland football final in 1933, losing to Mayo. Although emigration returned in the 1950s, the 1960s saw a strengthening of football in Donegal and, in 1972, they celebrated their first Ulster senior football title. The county’s first All-Ireland title came in 1992. In 2011 and 2012, Donegal succeeded in winning back-to-back Ulster senior football titles. Four under-21 Shield titles since 1999 also underline the progress being made in hurling.

An extract from MacCumhaill Park's purchase fund in 1947. ©GAA Oral History Project

Noreen Doherty, b. 1957

Noreen discusses being the first female county secretary and the reaction at her first county board meeting.

Naul McCole, b. 1939

Naul describes the great rivalry between Dungloe and Gaoth Dohbair and recalls the famous 'four matches' between the clubs in the championship during the 1950s.

'Then it [emigration] happened again in the sixties. I know whenever I was playing in Birmingham, we had about two dozen fellas from Carn… all local lads and it was the same in every parish then, they were just going away.'

- Paddy McClure, b. 1942

©GAA Oral History Project

'We walked to local matches and paid a shilling for admission. The county matches were five shillings to attend and we would travel by car, as many people as could fit. We always wore our Sunday best going to matches.'

- Gerald Timoney, b. 1934

©GAA Oral History Project

'We travelled all over Ireland supporting Donegal and I especially remember the run up to the 1992 All-Ireland and the subsequent celebrations. I remember brining tea and sandwiches to matches and usually getting to eat on the way home… If any of our clubs or county won any major honours I remember doing a parade down the main street in Letterkenny in cars with the horns beeping.'

- Sally Anne Boyle, b. 1981

©GAA Oral History Project

Down clubs, Castlewellan and Longstone, in action in the Kilmacud Crokes All-Ireland Club Sevens in 2009. ©GAA Oral History Project

Down was the first county from Northern Ireland to win an All-Ireland football final. The victory over Kerry in 1960 marked the culmination of a project that began in the 1950s. Down retained the title in 1961 and claimed their third title in 1968. These All-Ireland victories were accompanied by twelve Ulster final appearances in a row between 1958 and 1969, with the Mournemen lifting the cup on seven occasions. Although the GAA in Down was not as deeply damaged by the Troubles as it was in other counties, tensions still existed. A fractious relationship between the security forces and many members of the GAA had a lasting effect. 1991 saw the return of the Sam Maguire to Down, a victory which was followed three years later with the defeat of Dublin in the 1994 All-Ireland final. Although Down has enjoyed modest success in hurling – it has four Ulster senior titles to its name – the county remains primarily identified with Gaelic football. Recent growth in the local club scene has seen success at Under-21 level in both hurling and football and this growth was rewarded with an All-Ireland senior football final appearance in 2010.

Front cover of the programme for a match between Down and Armagh, the first inter-county football to played under lights. ©GAA Oral History Project

Tom Cunningham, b. 1946

Tom from An Ríocht GAC discusses the rivalry that existed between Kikeel and Greencastle and how the latter stormed the stage after a local sevens' final.

Máirín McAleenan, b. 1971

Máirín from Liatroim Fotenoys GAC discusses the pride she felt receiving a jersey from Sheila McCartan and talks about her All-Star.

'I think the club means everything to, let's be honest about it, the Nationalist people. It was the thing that kept us together when times were difficult. I'd argue it also kept people sane because if you hadn't have had the club there, there's a chance that a lot more people would've gone down the armed struggle way.'

- PJ McGee, b. 1950

©GAA Oral History Project

'There would've been disputes about the club here... whenever you went away to a match, Ballycranna would sit there, Ballygalet would sit there and Portaferry would sit here. We didn't speak to one another. That was just the way it was.'

- William Coulter, b. 1946

©GAA Oral History Project

'The vision and commitment of our club committees; their enthusiasm, their commitment to their communities, the great energy they bring to a community, the enthusiasm, colour, noise, the whole life experience of the community. I think our clubs are magnificent in what they're doing in terms of their activities for young and old and in terms of their facilities. I'd be very proud of that.'

- Dan McCartan, b. 1946

©GAA Oral History Project

Dublin take on Tipperary in the All-Ireland Camogie final in Croke Park in 1965. ©Cumann Camógaíochta na nGael

Although not the birthplace of the GAA, Dublin was the county in which the organisation was conceived and it is where it began to develop into the Association we know it to be today. Prior to the formation of the GAA in Thurles in 1884, Michael Cusack established two hurling clubs in the capital, the Metropolitans Club and Cusack’s Academy. It is from the Metropolitans Club that the idea for the Association emerged and it would be in Dublin – at Croke Park on Jones’s Road – that the Association would later establish its headquarters. Croke Park came to figure in the Irish public consciousness as more than a mere sporting arena as, owing to the events of Bloody Sunday in 1920, it became bound up with the memory of the nationalist struggle for Irish independence. Croke Park would also, of course, become a place of pilgrimage for GAA supporters attending major games in the capital. Indeed, a key feature of the development of the GAA in Dublin has been the contribution of those people from the country who settled in the city. Migration from rural Ireland helped swell the population of Dublin and as the county expanded to accommodate this influx, so too did the GAA. In all, Dublin has lifted the All-Ireland in football on twenty three occasions, most recently in 2011. While football remains the most popular Gaelic code, a significant investment of money and effort in recent years has seen a marked improvement in the quality of hurling in the capital – an improvement that manifested itself in the recent successes of Dublin underage teams and the county’s triumph in the senior National Hurling League in 2011.

A programme for a sports day organised by Round Towers G.A.C. in Clondalkin in 1926. ©GAA Oral History Project

Anne Maire Smith, b. 1977

Anne Marie recalls her Cavan-born father's reaction to her decision to support Dublin and describes what the GAA means to her.

Andy Kettle, b. 1946

Andy talks about the regular family trips to Croke Park during the championship and getting to see all the great players firsthand.

'I remember looking forward to going to matches; I would be full of excitement when I was younger awaiting a game. I felt it was my role or duty if you will to show my support for my county. I was representing Dublin, all kitted out in blue. I remember my mother would pack sandwiches for the trip to the game when I was a young boy. My father would have me on his shoulders during the match cheering away waving whatever merchandise we had bought of sellers outside. It was always a big deal and a day out at the match. As i grew older I still loved the anticipation, the adrenaline rush of watching the game.'

- Thomas Doyle, b. 1951

©GAA Oral History Project

'I remember originally supporting Kerry (where my dad is from) but after attending a National League Final in the late 1980s when Dublin beat Kerry, I decided to ditch Kerry in favour of my home team Dublin. How wrong I was - years of heart break and anguish later!

- Marcus Ó Buachalla, b. 1981

©GAA Oral History Project

'The GAA makes me very proud to be Irish, it makes me feel that this country is unique in the world today because we have something special. It's the soul of the people... it's the very essence of the fibres that make us all Irish... it's in our genes, it's going back to Cúchulainn and the hurley stick, we're going back 2000 years... it's all there.'

- Padraig O'Toole, b. 1950

©GAA Oral History Project

Ulster Council representatives carry a Fermanagh banner during a GAA centenary parade in Enniskillen in August, 1984. ©Fermanagh Museum

Early forms of Gaelic games existed in Fermanagh before the GAA established itself in the county in 1887. Although ‘camán’, an early form of hurling, was played, it was football which took hold in Fermanagh; by 1888 there were fifteen active clubs around the county. A decline in participation in Gaelic games during the difficult 1912-1923 period was followed by an equally impressive growth during the mid-1920s. Emigration and economic hardship during the 1940s saw a collapse of the club structure in the county; by 1950 there were only four clubs in the senior football league. And yet the decade that followed saw a rebirth of the GAA in the county and in 1959 Fermanagh celebrated an All-Ireland junior football victory. Despite the onset of the Troubles in the 1970s, coupled with the continued problem of emigration, club football in Fermanagh remained relatively strong. Although a first Ulster title has so far proved elusive, Fermanagh’s most successful run in the All-Ireland senior football championship to date came in 2004 when (using the back-door system to their advantage) they overturned the might of Armagh in the quarter-final before losing narrowly to Mayo in a semi-final replay.

An article from the Fermanagh Herald in 1968 showcasing the county's top club footballers. ©James McCaffrey

Malachy Mahon, b. 1930

Malachy talks about the excitement and the prepartations that took place in advance of Irvinestown's appearance in the Fermanagh Junior Championship Final in 1940.

Rita Traynor, b. 1933

Rita recalls playing for the Fermanagh hurling team in a friendly county match because the team was short for numbers.

'My grandfather was a founder member and player with Roslea Shamrocks in 1888... Living on a farm was seven days a week, but Sunday afternoon was always reserved for football matches... As transport was in short supply we would be packed about ten in a car. A bus would usually be hired for finals. I usually cycled to Ulster finals in Clones.'

- Bernard McCaffrey, b. 1951

© GAA Oral History Project

'Clubs didn't have very much money, so buying a set of jerseys was a big expense... we changed to maroon because the simple reason being that there was four or five of the leading members of the club at the time were enamoured with the great Galway team that won the three in a row and Galway wore maroon. So it was decided that 'well if it's good enough for Galway it's good enough for Tempo'.'

- Damien Campbell, b. 1946

© GAA Oral History Project

'That's the way the GAA is: it steps from generation to generation, it keeps everybody happy, and everybody has a topic of conversation from one end of the week to the other. We read the local paper here to see what happens and we look forward to it... we look forward to the weekends of the GAA. That's what being a member of the GAA, and what the GAA is to me.'

- Pat Chapman, b. 1941

© GAA Oral History Project

The Dervan brothers from Tynagh who all played on the same team in the late 1960s. ©GAA Oral History Project

It was following the abandonment of a match between Michael Cusack’s Metropolitan hurling club and the hurlers of Killimor in Ballinasloe due to ‘rough play’ in 1884 that the need to regulate the game of hurling on a national basis became apparent. Indeed, it was in Galway, and not Tipperary, that Cusack initially planned to establish the GAA. The Association, and in particular hurling, thrived in the county from the offset. This is evident from the participation of fourteen clubs and ten thousand spectators in a tournament in Clarinbridge in 1887. The county’s first All-Ireland hurling title came in 1923 and despite further promise it was only in 1980 that the feat was replicated. Since then, Galway has added two more titles, bringing their total to four. Despite the absence of further All-Ireland honours in the intervening years, Galway club sides, most notably Portumna and Clarinbridge, have proved prolific in national competitions. Galway also has an impressive footballing record, achieving All-Ireland success on nine occasions, including a three-in-a-row in the 1960s. They remain among the country’s most active dual code counties.

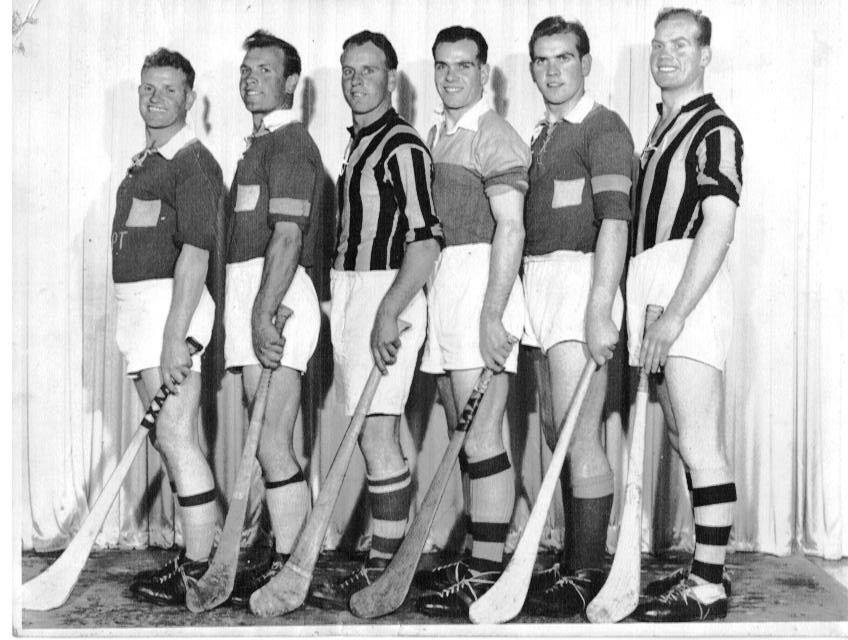

A membership card for Dunmore McHales GAA Club, dated 1891. ©GAA Oral History Project

Michael McGowan, b. 1936

Michael recalls organising a 22 a-side school game in Lough Rea that was played on the frozen lake.

Arthur Ó Flaithearta, b. 1953

Pléann Arthur tréimhse rathúil a bhí ag Naomh Éinne, Inis Mór ag tús na n-ochtóidí.

'I was brought up in a GAA household. When I was about 18, for the first time in Galway, ladies football commenced with two clubs forming, one was Belclare and the other Caherlistrane. So myself and my two sisters started playing with Caherlistrane, because it was the nearer club to us. My earliest GAA memory was going to an uncle's house to watch Galway play in the All-Ireland Football Final of 1964. At that time few people had the luxury of a television set. We were lucky in that my uncle who lived down the road had one and I remember his house being full with all the neighbours in looking at the match.'

- Geraldine Kennedy, b. 1958

© GAA Oral History Project

'It was most exciting for me when I was younger, travelling to the big county games and to me, county players were all my heroes. Among the grounds which we visited frequently were Tuam Stadium, MacHale Park, Castlebar, Markiewicz Park, Sligo, Páirc MhicDhiarmada, Carrick-on-Shannon and St. Coman's Park, Roscommon. We were fanatical supporters who wore our county colours and who rejoiced in our victories and were shattered when defeated.

- Leo Finnegan, b. 1944

© GAA Oral History Project

'Back in the 1980s there were very few TVs on the island [Inisbofin], so we used to meet up in this particular house to watch the games, especially when Galway were playing. [We] used to have good craic with the old men who were also watching the game. In later years, [we] travelled to Connacht Finals and if we were lucky to All-Ireland finals.'

- Anne Walsh, b. 1959

© GAA Oral History Project

Patients of St Finan's Hospital who were involved in the construction of Fitzgerald Stadium in Killarney during the 1930s. ©GAA Oral History Project

Kerry is the most successful county in the history of the Gaelic football, winning All-Ireland titles on 36 occasions. The prominence of football can be somewhat attributed to the local traditions of ‘Caid’, a form of folk football played in Kerry long before the establishment of the GAA. The faltering progress of the GAA in rural areas of Kerry in the late 1890s due to emigration was countered by the rejuvenation of the Association in towns such as Killarney and Tralee in the early twentieth century. Kerry’s first All-Ireland football title was won in 1903 and many more followed. The preeminent force in the game, Kerry twice won four All-Ireland titles in a row: from 1929 to 1932 and from 1978 to 1981. In Kerry, the football tradition has constantly been reinforced. Success has built upon success. As if to emphasise the point, the county appeared in nine of the first twelve All-Ireland finals played in the new Millennium.

A programme for the opening of Con Brosnan Park in Moyvane, Co. Kerry in June 1984. ©GAA Oral History Project

John Bambury, b. 1924

John recalls his first experience on the 'ghost train' from Killarney to Dublin in 1939.

Sean Kelly, b. 1952

Former GAA president Sean Kelly talks about the time his brother snuck out of the priests' college in Maynooth to come home to play a local final.

'Being a Kerryman, football is a second religion in the county so it was unavoidable to escape it. Watching Kerry teams training in Killarney, my home town, from the '50s onwards leaves a a lasting impression.'

- Aloysius 'Weeshie' Fogarty, b. 1941

© GAA Oral History Project

'Matches in Killarney were a nightmare with traffic. Today's tradition is to get there early settle in a pub near the ground and build up the atmosphere to a point where you talk your stomach into knots with nerves. Time to go then.'

- Peter O'Regan, b. 1980

© GAA Oral History Project

'But the fields were very poor like you know, there was no such thing as fields being lined, some places there was a rope across for a crossbar. Then you'd have umpires and when a score was coming towards the post, they'd pull it in or pull it out to make sure that it went wide or went over the bar.'

- Billy Doolin, b. 1945

© GAA Oral History Project

The 1928 Kildare football team who were winners of the inaugral Sam Maguire trophy. ©GAA Oral History Project

Kildare was central to the early popularisation of Gaelic football, with the three games the county played with Kerry to decide the 1903 All-Ireland final drawing huge crowds and generating widespread excitement. That 1903 final, played in 1905, came in the wake of the reorganisation of the GAA in Kildare in 1901 and followed a decade of decline in the 1890s. Although ultimately defeated in the 1903 final, a first All-Ireland title followed when Kildare defeated Kerry in the 1905 final – a game not played until 1907. A second All-Ireland title was claimed in 1919 and, following back-to-back titles in 1927 and 1928, Kildare became the first county to be awarded the new Sam Maguire trophy. This success, coupled with the influence of the Curragh military camp, saw the emergence of new teams in the county in both football and hurling. Between 1930 and the late 1990s, however, Kildare would win only four Leinster titles. Massive population growth since the 1970s, particularly in the towns and villages of the north of the county, presented the GAA with new challenges and opportunities. In towns such as Leixlip, clubs adapted to the new social realities, assisting – through the provision of key sporting and social outlets – in the forging of new, vibrant communities. For all that there has been extraordinary change, Kildare’s search for a first All-Ireland title since 1928 remains ongoing.

A colourful programme from a game in Newbridge between Johnstownbridge and Athy in 1987. ©GAA Oral History Project

Séamus Aldridge, b. 1935

Séamus talks about the impact of the Second World War on the GAA in Kildare and the contribution of the local army barracks to surrounding area.

Mary Weld, b. 1949

Mary discusses her various administrative roles in the GAA in Kildare and recalls her first experience at a county board meeting.

'We would drive on up in the bus, stop outside the picture house in the Curragh. One of the girls would go in and take out three of four girls out of the picture house and say "You're comin with us" and we'd go on to play the match. It was brown gym frocks, pink blouses, black tights – you’d always have a few spare ones in the van going…And then the girls would be getting on the field and they'd say "Hey Mag, what's my name today?"'

- Margaret Sexton, b. 1948

©GAA Oral History Project

'Football had a big influence on the jobs...If you were a footballer, you got into ESB. If you were a footballer, you'd get into Roadstone. If you were a footballer, the Irish Ropes here in Newbridge, but you could only play with Moorefield. There's two teams in Newsbridge: Sarsfields and Moorefield... The Ropes was Moorefield dominated. Lads from other clubs, if they wanted a job in the Irish Ropes, they had to transfer to Moorefield.'

- Tom Moore, b. 1949

©GAA Oral History Project

'One of my most treasured memories is my first game in Newbridge in the U-10 final in 1987. I was playing corner forward that day and we won. It meant the world to us to be playing in the county grounds and then to actually win was amazing. I can remember calling over to my granny's house after the match and also receiving our medals from Pat Dunney at a function in the clubhouse.'

- Enda Gorman, b. 1978

©GAA Oral History Project

Team captain Seamie Cleere is presented with the Liam McCarthy Cup by Eamon de Valera after the 1963 All-Ireland final. ©GAA Oral History Project

Kilkenny is the most successful county in the history of the All-Ireland hurling championship. Although it was football that initially thrived in the county – the first football game played under GAA rules took place in Callan in February 1885 – hurling later became the main Gaelic sport in the county following the securing of the county’s first hurling title in 1904. Over the following decades, hurling success and Kilkenny went hand in hand. For example, from 1931 to 1939 the county contested seven All-Ireland finals, winning four of them. Of great benefit to Kilkenny was the constant stream of players from the county’s schools and colleges, many of which enjoyed a thriving hurling culture. Pre-eminent among them was St Kieran’s, which served as a conveyor belt for some of the greatest hurlers in modern history, including Eddie Keher, DJ Carrey and Henry Shefflin. Brian Cody, another St Kieran’s graduate, has brought remarkable success to the county in recent times. In the opening decades of the twenty-first century, Kilkenny won seven All-Ireland titles and only Tipperary stopped Kilkenny from completing an unprecedented five-in-a-row in 2010. The following year saw Kilkenny regain the Liam McCarthy Cup from Tipperary, their 33rd All-Ireland title.

The match programme from the 1966 All-Ireland hurling final in which Cork beat Kilkenny 3-9 to 1-10. ©Donal Dalton

Nickey Brennan, b. 1953

Former GAA president Nickey Brennan discusses why he gave his support to the setting up of the GAA Oral History Project.

Seamus Reade, b. 1947

Seamus recalls how inexpensive it was to take up handball and how some games were made more interesting by betting.

'Rivalries are crucial in the GAA. My club have many rivalries with neighbouring clubs, such as Thomastown and Danesfort. Mostly Danesfort as we have lost many players to them due to the dreaded parish rule. It has not been kind to us.'

- Hugh O'Neill, b. 1933

©GAA Oral History Project

'The 1972 All-Ireland final was the best I've ever seen. Kilkenny played Cork and Kilkenny came from eight points down to win by seven... The hurling was magnificent with great stars like Eddie Keher, Frank Cummins and "Chunky" O'Brien.'

- Eugene Larkin, b. 1952

©GAA Oral History Project

'There were great competitions in hurling... and there were great leagues. And when you were in Kieran's you'd nothing else to do only play hurling or play football leagues and the whole lot. Now my young lad is just after coming through Kieran's... and sure, not unless you're on the elite would you be doing any hurling.'

- John Phelan, b. 1952

©GAA Oral History Project

Laois face Tipperary in the 1949 Oireachtas Final. ©GAA Oral History Project

Appearances in two consecutive All-Ireland hurling finals in 1914 and 1915, with a victory in the latter, were early milestones in the GAA story in Laois. A mixture of skilled administrators and the establishment of schools’ leagues helped reverse faltering participation that had occurred within the local Association in the late nineteenth century. If hurling was the game in which the Laois reputation on the national sporting scene was forged, it would soon be eclipsed by football. The decline in hurling’s profile was not helped by the failure of the county to win a single Provincial title between 1950 and 2012. For their part, the Laois footballers made history in 1938 by becoming the first team from Leinster to tour the United States. This came during a high point for football in Laois, with the county winning three Leinster titles in a row between 1936 and 1938, and another in 1946. It was not until 2003, however, that the county added to their Provincial tally, doing so under the guidance of Mick O’Dwyer. A real success story in Laois has been the growth of ladies’ football. The establishment of a county board for ladies’ football in the 1970s marked a watershed for the women’s game. The sport flourished in the county and in 2001 Laois overcame Mayo to win their first All-Ireland ladies’ title.

An advertisement for a fundraiser in aid of Durrow GAA in 1983. ©GAA Oral History Project

Paddy Bates, b. 1942

Paddy talks about playing hurling during lunch time in school in Clonaslee and how sometimes they lost track of the time.

Gerry Cullitin, b. 1936

Gerry discusses receiving a ban from the Laois county board after they discovered he played a rugby match for Tullamore.

'The introduction of ladies' football and the expansion of Camogie has been the single most influential factor in the GAA. With these games, and particularly football, the active membership of the GAA increased spectacularly and a whole new surge of able and dynamic members began to participate in all levels of club activity.'

- Fintan Walsh, b. 1936

©GAA Oral History Project

'I remember the first county final with our club in it. Dressing up in the red and white and making flags and banners, every teddy was taken out of the press and every ball of wool was used. We all headed to behind the goal posts to shout our team on. They lost but I still never forget the village that evening when they came through on the back of a trailer and tractor.'

- Cathyrn Foyle, b. 1977

©GAA Oral History Project

'Back in our own club when we started we had two big jobs up in our area up in Camross, in timber... All our lads worked in the forestry and Bord na Móna... that kept all the clubs here. We were fortunate enough lads didn't have to emigrate or go away like that. Now the forestry's gone... the timber's gone and Bord na Móna is completely nearly gone as well and now emigration is hitting a lot of clubs and hit Camross in a big way... not in Camross alone but a lot of clubs are feeling the pinch... Hopefully if the building could take off again we might get back players.'

- Frank Keenan, b. 1951

©GAA Oral History Project

A county calender featuring the Leitrim team that won the 1927 Connacht Championship. ©GAA Oral History Project

Although Leitrim has the smallest population of any other county in Ireland it can boast the highest number of GAA clubs and players per capita (twenty-four clubs in total as of 2010). The decline in the GAA’s fortunes in the 1890s was a national phenomenon, but it had a major effect on many of the smaller counties, such as Leitrim. The formation of a new county board in 1904 saw the expansion of the Association throughout the county, resulting in a renewed and vibrant club scene. Emigration, however, has played a critical role in the ability of Leitrim teams to compete on the inter-county scene. A population decline that began in the mid-nineteenth century continued until the 1990s, at which point the population of Leitrim stood at approximately 25,000. For all its obvious disadvantages, Leitrim has enjoyed some notable successes. Highlights include the winning of an All-Ireland ‘B’ football title in 1990 and an Intermediate All-Ireland Ladies football title in 2007. The vitality of the GAA in the county is also reflected in the contribution it has made to the development of the Scór competition, where Leitrim members have enjoyed considerable success.

A poem written by Johnny Mulhern about the 1988 All-Ireland Junior ladies' football champions. ©GAA Oral History Project

Mary Glancy, b. 1956

Mary recalls her time as county secretary and the difficulties in contacting players before the time of mobile phones.

Tommy Moran, b. 1941

Tommy talks about the make up of the GAA in Leitrim and discusses the loyalty of the players to the county team.

'Somebody said to me, "what was your first thought when you won the All-Ireland in 1988 and you're standing in the middle of Croke Park...?". My first memory was "where is the ball? Get it and put it back in the bag. Don't lose any of our stuff!"... You had to work so hard to get money to get jerseys, to get balls. You minded it when you had it.'

Mary Quinn, b. 1958

©GAA Oral History Project

'Leitrim, as a county, has been deprived of success at a national level but that doesn’t dampen the enthusiasm or commitment or the work of everybody that’s involved in whatever capacity. They embrace it.'

Joe Flynn, b. 1947

©GAA Oral History Project

'The football was made up of rags that were tied with a rope and played. That was our football. Sometimes the pig's bladder was used as well, but that was only at Christmas and, of course, inevitably it would get punctured... on a blackthorn stick or something like that... So that would end that football and we'd have to go back to the rags again.'

Michael McGowan, b. 1936

©GAA Oral History Project

Limerick face Tipperary in the 1937 Munster final in Cork. Tipperary were winners on the day. ©GAA Oral History Project

In keeping with the experience of many counties, the GAA in Limerick suffered a decline in the late nineteenth century. Its recovery would be quicker than most, however. The establishment of a new county board in 1894 was quickly followed by All-Ireland success in both football and hurling. Of the two codes, hurling would establish its pre-eminence in the county in the early decades of the twentieth century. The county won All-Ireland titles in 1918 and again in 1921, but the 1930s represented the true heyday of Limerick hurling. Five National League titles in a row were won, as were two All-Ireland titles, with a third added in 1940. Owing to emigration and other factors, this tradition of success could not be maintained and it was only in 1973 that Limerick’s hurlers won their next All-Ireland title. This remains their most recent national title. Despite the stiff competition faced by the GAA from rugby, particularly since the onset of professionalism and the success of the Munster Rugby team, important steps have taken by the local Association – manifest in the improvements to club and county facilities – to secure a healthy future for Gaelic games in the city and wider county.

Members of St Munchin's GAA Club appeal for money for their new field, Seoirse Clancy Memorial Park. ©GAA Oral History Project

Liam Lenihan, b. 1950

Liam talks about his involvement in the 'Lifting the Treaty' project; a project aimed at encouraging the playing of hurling in Limerick City.

Paul Herr, b. 1973

Paul discusses the popularity of handball in his home town of Hospital and in the rest of Limerick.

'Have great memories of going to games all six of family – parents, two sisters and brother in a small Anglia. Food would be consumed on the side of the road. Colours hung out and horns etc. blown at friend and foe. Many tears were shed on days of disappointment but the joy of winning was unbelievable and the Munster Hurling Final of 1973 will never be forgotten.'

- Gearóid Ó Súilleabháin, b. 1956

©GAA Oral History Project

'The highlight of our day, our week and our night was to go out for a puck, you’d have your stick stuck at the back of the gate somewhere because if someone found it he’d take it and you’d have no stick to go out for a puck.... It’s our stamp, the GAA is really our stamp it’s the rural man’s stamp, right, it says who he is like, what you stand for, right, where your spirit comes from, you know, ‘tis your freedom, you know, there’s nothing as good to hear or to do than to have a fair clash with the ash there like and to win an aul ball, d’you know and the other fell will enjoy it even though he might lose it, it doesn’t matter, but that’s the way it is like.'

- Micheál Mac an tSaoir, b. 1946

©GAA Oral History Project

'Ceapaim go bhfuil an CLG an-tábhachtach dúinn mar chlann, réitimid go maith lena chéile agus is é mo thuairim go bhfuil sé sin de bharr an páirt a bhí ag an CLG inár saoil.'

- Theresa Corbett, b. 1988

©GAA Oral History Project

Boys from a local team in Longford tog out in a nearby bush before the start of the game. ©GAA Oral History Project

With the national decline of the GAA in the 1890s, the Association in Longford was reduced from a vibrant organisation of twenty five clubs with over a thousand members to an almost non-existent entity. By the time the local GAA revived in the early 1900s, soccer had established itself as a dominant game in the county’s principal urban centre. As the GAA slowly regained lost ground, the preference for football over hurling in the county became apparent, not least in colleges such as St Mel’s, winners of the inaugural Leinster colleges’ competition in 1928. Longford experienced massive levels of emigration in the years following the ‘Emergency’ and though the GAA was affected at a local level, the effect on the county team was not immediately apparent. In fact, the 1960s was Longford’s most successful period. A first National Football League title was won in 1966, followed by a Leinster title in 1968. Success since then has centred on the county’s underage teams where investment in youth structures has delivered two Leinster minor football titles to Longford since the turn of the new millennium.

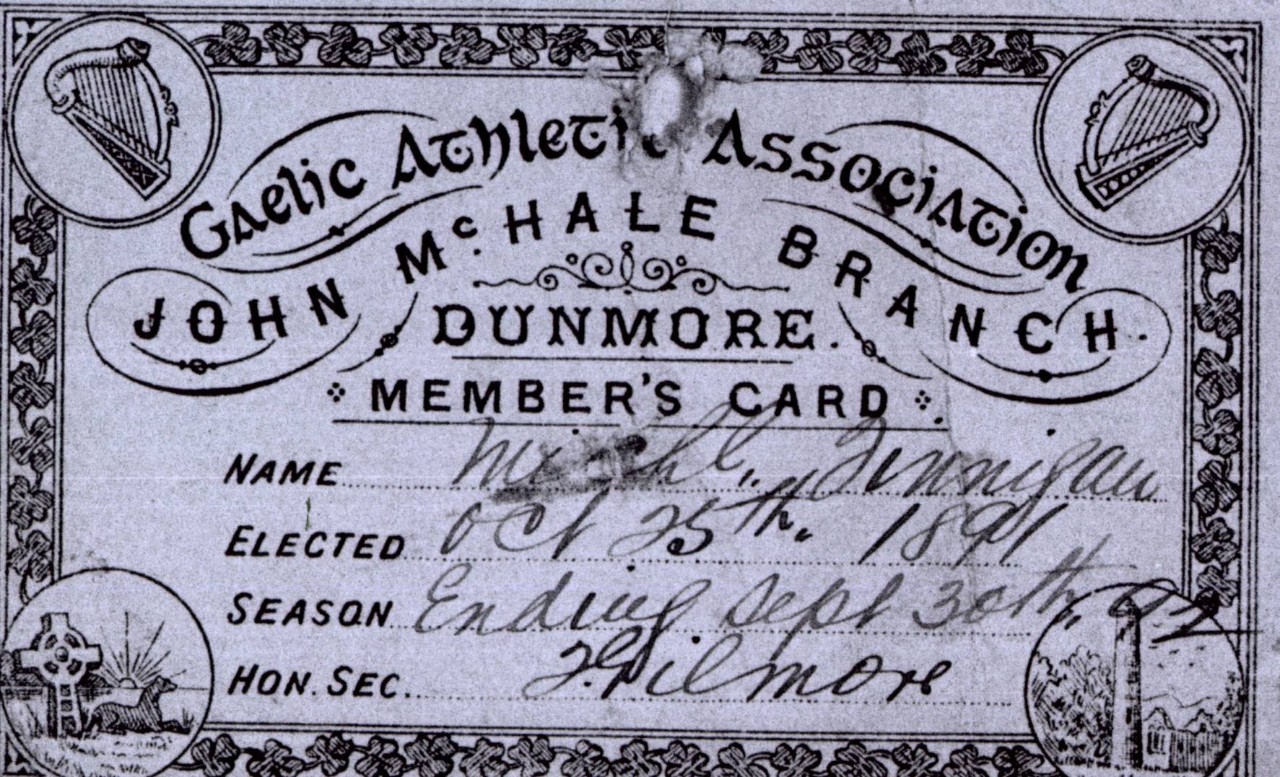

A poem about the former player and Director General of the GAA, Liam Mulvihill, written by Paddy Egan. ©GAA Oral History Project

Eugene McGee, b. 1941

Eugene discusses the success of Longford's footballers during the 1960s and the role his brother played in that success.

©GAA Oral History Project

Martin Jennings, b. 1948

Martin talks about how hurling has fared in Longford over the years and the improvements he has seen in recent years.

©GAA Oral History Project

'The GAA was very important in our house when we were growing up. We were brought to nearly all the Granard and Longford games and always encouraged by both our parents. Every Sunday the car was loaded up and we headed off to where ever Granard were playing. During Summer school holidays the only time we would get off the farm was mass on the Sunday and football training and matches. Most things were planned around the football.'

- Matt Smyth, b. 1963

©GAA Oral History Project

'During the Rosary my mother always prayed for one of my brothers in particular... This is probably because he was prone to injury. I remember one time a Guard called to our house late on a Sunday evening to tell my mother that my brother had been taken to hospital with a broken leg following a match injury. She was glad neither herself nor myself managed to get a lift to that particular match. My brother was on crutches after that and I remember him playing in goals (even with his leg plastered) in the hay field at the back of the house.'

- Mary Hughes, b. 1956

©GAA Oral History Project

'If he got hurt, there was no way he could go home and tell. He put out his collarbone this particular day, and he got the coat on after the match but he couldn't get the coat off because the collarbone was dislocated and, he had to go out and plough the next morning and he couldn't take off the coat - and he didn't take off the coat for about three weeks afterwards. It must have been unreal, the pain that he went through. But they had to show that they were tough, and if they got hurt playing football there was certainly no sympathy for them at home.'

- Martin Skelly, b. 1953

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Fergal Kelly, b. 1976

The Sam Maguire Cup visits a local primary school in Louth following the county's 1957 All-Ireland football win. ©GAA Oral History Project

Louth’s winning of the 1957 All-Ireland football championship brought to an end a glorious half century of Gaelic games in the so-called ‘wee county’. 1957 had built on an established tradition. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the county repeatedly contested for provincial and national football honours, winning two All-Irelands in three years between 1910 and 1912. These finals had signalled the resurgence of the GAA in a county which, in keeping with the national trend, suffered serious decline in the early 1890s. Prior to that, the Dundalk Young Irelands, a club founded by the Young Ireland Society in 1885, contested the very first All-Ireland football final in 1887. Dundalk was a hotbed of early GAA activity in the county and, indeed, an urban-rural divide would remains a feature of the make-up of Louth’s All-Ireland winning teams of 1910 and 1912 – teams that were dominated by players from clubs in the urban centres of Dundalk and Drogheda. Although success at senior level has been absent since 1957, the GAA has continued to develop in the county. An increased investment in facilities, the introduction of ladies football and the establishment of a centre of excellence for county teams have all served to further embed the GAA into the community life of the county.

A letter from 1961 regarding the purchase of a ground by Dreadnots GAA through the Land Commission. ©GAA Oral History Project

Niamh Reid, b. 1990

Niamh talks about the need for increased publicity for Ladies' football and camogie and how the games would benefit if more people knew about them.

©GAA Oral History Project

Tommy Carroll, b. 1928

Tommy discusses the history of Dundalk Young Irelands and talks about the link between politics and the GAA in the past.

©GAA Oral History Project

'When that goal went in against Meath...I think that was the biggest disappointment. And the disappointment that expanded when I realised that within the GAA we had no format to handle that...I was disappointed that over all the years we've had there was no structure whereby the authorities could have stood up and said there: 'That's wrong. We're gonna have a replay'. Natural justice should have demanded that.'

- Padraic O'Connor, b. 1954

©GAA Oral History Project

'From a young age I realised that the GAA was a way of life, it was how my life was going to be… Every Sunday involved going to matches, going to training, watching the Louth County team train two, three times a week, going to club matches, helping out with the administration with my father at home in the house where his office was based... It's just all I've ever known.'

- Donal Kearney, b. 1976

©GAA Oral History Project

'We used to practice over in a field called the Castle Meadow, a mile or two away, and sure you'd be working here on the farm and sure you couldn't wait for night to come till you could get away...You'd hear the thud of the ball and you'd have to get away to that.'

- Willie Treacy, b. 1929

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Michael Mooney, b. 1946

Locals posing with the Sam Maguire in the village of Shrule following Mayo's All-Ireland win in 1951. ©GAA Oral History Project

With a strong local tradition of athletics, Mayo developed as the pre-eminent football power in Connacht in the early twentieth century, winning eight of the nine Provincial finals played between 1901 and 1910. For all this dominance, however, Mayo had, by 1932, appeared in only three All-Ireland football finals – and lost all three. The fortunes of the county at national level changed in the years that followed, with Mayo embarking on a phenomenal run of success, winning six National Football League titles in a row, as well as a long awaited All-Ireland title in 1936. Further provincial honours followed in the 1940s, but the peak of the county’s GAA achievements came in 1950 and 1951 when Mayo won back-to-back All-Ireland titles. These victories were remarkable for being achieved against a backdrop of economic deprivation and decline – the population of the county had fallen steadily since the mid-nineteenth century. Football retains a strong hold on the county and, despite falling at the final hurdle in five All-Ireland finals between 1989 and 2011, a vibrant club scene has delivered All-Ireland club titles to both Crossmolina and Ballina Stephenites since the turn of the millennium. Mayo have also been trailblazers in the women’s football game, with four All-Ireland titles already to their name.

A tick book used to mark the attendence of committee members of Balinrobe GAA in 1921. ©GAA Oral History Project

Terry Reilly, b. 1943

Terry recalls his early memories of the GAA and the influence that the All-Ireland winning Mayo team of the 1950s had on him as a journalist.

©GAA Oral History Project

Paddy Muldoon, b. 1941

Paddy talks about the history of Westport GAA and discusses the club's links with the republican movement of the early twentieth century.

©GAA Oral History Project

'The football boots, I remember... We didn't even have the boots. Times were rough in the fifties... If you knew a fella with a left foot you got his right foot boot if it fitted you. That's a fact. Things like that. Because we had nothing.'

- Mick Loftus, b. 1929

©GAA Oral History Project

'The advent of the Mayo women's teams has been most exciting as Mayo people have once again had the experience of winning All Irelands. The standard of women's football is very high, especially their ability in taking scores. I think many of the male players have got afraid of missing scores and are not adventurous there.'

- Anthony Jordan, b. 1942

©GAA Oral History Project

'Bhí dhá chreideamh i mBéal Átha hAmhnais, cé go raibh mise sna fichidí nuair a chonaic mé Protastúnach ariamh. Bhí eaglais an pharóiste ansin ag ceann an bhaile, ag an ceann eile den bhaile, bhí mainistir na nAgaistínigh; ba chosúil gur dhá chreideamh éagsúil iad…Bhí dhá chóir againn; bhí cóir ag sagairt an pharóiste, bhí cóir ag na hAgaistínigh. Bhí dhá chumann drámaíochta againn. Bhí feis amháin againn, á reachtáil ag sagairt an deoise; bhí feis eile, nó aeiríocht ag na hAgaistínigh. Bhí dhá misean againn in aghaidh na bliana. Caitlicigh iad gach duine ach ba chosúil gur dhá sect éagsúil iad ag an am. Só bhí foireann peile ag na hAgaistínigh chomh maith le haghaigh na buachaillí a bhí ag feithil ar an Aifreann agus mar sin de.'

- Joe Kenny, b. 1932

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Sean McManamon, b. 1939

Captain Brian Smyth holds aloft the Sam Maguire after Meath's 1949 All-Ireland win. ©Hogan Stand

As Secretary of the GAA from 1895 to 1898, Dick Blake from Navan oversaw the overhaul of Gaelic football, standardising the size of the ball, introducing linesmen to assist referees and fixing a goal's value at three points instead of five. It is not surprising that the sport that Blake did so much to shape should be the one most favoured in his native county. Gaelic football was enthusiastically played and followed in Meath from the early years of the GAA, yet it was not until the post-Second World War period that Meath finally claimed a first All-Ireland title. The first came in 1949 and was followed up by another title in 1954. The strength of Meath football during this period was further underlined by the county’s achievement in winning five provincial titles in the seven years between 1947 and 1954. The 1960s brought another All-Ireland football title to Meath and the successful team travelled to Australia in 1968 to compete against an Australian Rules selection. This tour, which followed an Australian visit to Ireland the year before, laid the foundation for the international compromise rules game that was officially established in the mid-1980s. In Meath, however, the 1980s are best remembered for the county’s re-emergence as a powerhouse in Gaelic football. From the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, the county won four All-Ireland titles, all of them under the charismatic stewardship of Dunboyne-man Seán Boylan. The massive levels of population growth that Meath experienced in the late 1990s and early 2000s has had a visible impact on the GAA in the county. As clubs expanded and membership increased, the Meath experience served to underscore the continued importance of the GAA to a changing Irish society.

A publication by Peter McDermott detailing Meath's trip to Australia in 1968. ©Peter McDermott

Michael Connaughton, b. 1942

Michael describes the atmosphere at one of the first meetings of St Brigid's G.F.C in the early 1960s.

©GAA Oral History Project

Peter McDermott, b. 1918

Peter recalls an on field incident between a friend and the local priest who was known for his republican leanings.

©GAA Oral History Project

'When the local team won it was always a great source of pride in Duleek, everyone in the village came out to celebrate and a band always played on the back of an articulated truck parked on the village green – everyone made speeches, there was always dancing and drinking on the village main street.'

- Frances Fahy, b. 1979

©GAA Oral History Project

'I'll never forget the year 2000... we won our first ever senior championship. To me that was the greatest day in the life of the club [Dunshaughlin] because... two or three years prior to that, we never saw ourselves as senior champions in this county renowned for football... and we achieved that.'

- Paddy O'Dwyer, b. 1945

©GAA Oral History Project

'I remember the Cork Meath, the '88 match, making a flag the size of the kitchen floor and saying 'Meath are magic, Cork are tragic' and coming out and crying. And up until three years ago I forgot why I didn’t like the colour red.'

Maria Kealy, b. 1984

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: John Gleeson, b. 1974

Camogie players from Toome GAA take a break during a game. ©Toome GAA

Within a year of the establishment of its county board in 1887, thirty two clubs were active across Monaghan – a rate of progress that, in Ulster, was only eclipsed by that of Cavan. It is even claimed that the Inniskeen club had been founded in 1883, a year before the foundation of the Association itself. Like much of the rest of the country, the GAA in Monaghan suffered decline in the 1890s, but a vibrant club scene developed in the early twentieth century. With the Castleblaney Faughs club in the local ascendancy in the years which followed the establishment of the Irish Free State, Monaghan would enjoy one of its most successful eras. Ulster titles were won, for instance, in 1927, 1929 and 1930. The GAA struggled in Monaghan in the decades that followed, its efforts undermined by the scourge of emigration, with the county losing 10% of its population between 1956 and 1961 alone. Despite this haemorrhaging of people, those who remained came together to win a junior All-Ireland title in 1956. In the 1970s and 1980s, improvements off the field were matched by success on it. Monaghan would bridge a gap of more than forty years to regain the Ulster title in 1979 and though further titles were added in the 1980s, senior All-Ireland football honours continued to elude the county. In the 1990s, however, the county’s hurlers secured a junior All-Ireland hurling title, while the Monaghan Ladies’ won the senior All-Ireland titles on two occasions.

A list of rules and bye-laws for a summer street league in Monaghan in 1922. ©GAA Oral History Project

Paul Swift, b. 1965

Paul recalls an incident involving jerseys the night before the first county final in Monaghan between Monaghan Harps and Aghabog.

©GAA Oral History Project

Pat McEnaney, b. 1961

Pat talks about the amalgamation of local rivals Corduff and Carrickmacross at underage level in his time and the different perceptions of players from the country and those from the town.

©GAA Oral History Project

'When I was younger, I remember coming across a photo of the local hurling team in the newspaper and looking at the names underneath. I recognised several of the local Patrician Brothers but the names under the photo didn't match! When I enquired about this, I was told that they weren't supposed to be playing hurling and that they had to play under 'assumed' names!'

- Marriane Lynch, b. 1959

©GAA Oral History Project

'I walked 3 miles to practice and back. The field was very uneven. The game of football rough and physical. Our shorts were very long and jerseys had long sleeves. Not many people came as spectators. The football was very heavy when it got wet as it absorbed water.'

- Maurice Coyle, b. 1940

©GAA Oral History Project

'I would have been one of the first in our end to get a car and I remember I used to - there was meself and the brother - we'd start off, go over and pick up Brian Coleman - that's three - go up pick up two Hughes - that's five - up to the crossroad - there could be two or three Donaghys standing on it - and you got as many in as you could and headed off. And had we had anything happen Toome wouldn't have been fit to field a team that day cause half of us would have been missing.'

- Enda Quinn, b. 1957

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Bill Lynch, b. 1951

Mick Spain helps put the finishing touchs to Drumcullen GAA's new grounds in 1984. ©GAA Oral History Project

Offaly played host to the first All-Ireland hurling final played in Birr on Easter Sunday, 1888. Then known as King’s County, Offaly had been involved in the GAA from the very beginning with Clara being only the third club in Ireland to affiliate to the new Association. Geography was a key determinant in how Gaelic games developed in the county. Whereas hurling prospered in the south of the county, football dominated in the north. By the early 1900s there were twenty five Offaly clubs affiliated to the GAA and this number would rise steadily across the decades that followed. For all that this illustrated the local enthusiasm for Gaelic games, success was limited. Nevertheless, the development of state bodies in Offaly during the mid-twentieth century would play a crucial role in the advancement of the Association, providing employment and keeping potential players in the county. The 1960s signalled the beginning of a period of unprecedented success for Offaly in both hurling and football. The county’s first senior All-Ireland football title in 1971 was followed by six more over the next three decades, two in football and four in hurling. Offaly has since slipped in terms of success and it has been down to the county’s camogie players to provide cause for celebration in recent years.

A poem celebrating the Offaly's 1985 All-Ireland hurling victory. ©GAA Oral History Project

Emily Horan, b. 1920

Emily recalls her first experiences of playing camogie and describes how some matches were very rough.

©GAA Oral History Project

Sean Flynn, b. 1937

Sean describes walking along the train lines to an Offaly match in the 1950s after the train broke down en route.

©GAA Oral History Project

'Luckily for me, I was fortunate enough to have grown up in a era where Offaly GAA was very successful. My first time on a train was accompanying my father to the Leinster hurling final in 1980. There was no such thing as replica jerseys then, just rosettes and hats made from crepe paper.'

- Pádraic Tooher, b. 1966

©GAA Oral History Project

'A tradition that our family used was that every one of us playing GAA wore a miraculous medal on our togs and also my mother would throw holy water on the gear bag when leaving the house. She was a very holy woman and she believed it kept us safe when we played and I keep that tradition alive to this day.'

- Mary Kelly, b. 1958

©GAA Oral History Project

'My father told me about when he and his brothers used to play and the great games he saw. When he was playing full back one day he was marking a big tough man that a lot of people called mad. When his marker walked out he had a bottle of whiskey in his togs and he took it out and drank it in one go and pucked it out over the bar and said to my father, "When the first ball comes in, that’s where you’re going." But when the first ball came in he went to catch it but my father hit it out and the mad man never spoke during the match again.'

- Frank Cashen, b. 1959

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Pat Nolan, b. 1982

The Sam Maguire rests on a stool in the village of Knockcroghery after Roscommon's All-Ireland win in 1943. ©GAA Oral History Project

While there was GAA activity in Roscommon in the late nineteenth century, it took until the early twentieth century for the county to enjoy success at a representative level. Several Connacht football titles were won during this period, as was a hurling title in 1913 – this remains the county’s only Provincial hurling success. Football was, and remains, the Gaelic sport of choice in the county, its popularity bolstered in the 1940s by the winning of back-to-back All-Ireland football titles in 1943 and 1944. Such success, yet to be repeated, was helped by administrative improvements in the county and the emergence of Roscommon CBS as a serious conveyor belt of local football talent. Efforts to build on the achievements of the 1940s were undoubtedly hampered by a declining agricultural economy and emigration. So while Roscommon managed to win at least one Connacht championship in each decade since the 1940s, no further All-Ireland titles have followed. Against that, the county’s hurlers have twice won an All-Ireland junior title while the ladies’ football team claimed a senior All-Ireland title in 1978.

A letter from the 'Roscommon exiles in Manchester' to Jimmy Murray congatulating him on the county's All-Ireland win in 1944. ©GAA Oral History Project

Tony Whyte, b. 1937

Tony recalls Clann na nGael's journey to the All-Ireland club football final in 1982.

©GAA Oral History Project

Frank Kenny, b. 1934

Frank discusses the history of St Brigid's GAA and talks about how the club came close to disbanding in the 1950s.

©GAA Oral History Project

'No Sunday dinner for there was always a GAA match to attend. Not much work done on evenings as training was number one.'

- Martin Hynes, b. 1937

©GAA Oral History Project

'I always loved football but unfortunately there were no girl’s teams in our area in the '60's or '70's. When Roscommon got to the All-Ireland in 1980 we had a great time going to Croke Park for the matches. In recent years, I encouraged my children to play and we are always planning some trip to a match.'

- Anne (Née McHugh) Walshe, b. 1959

©GAA Oral History Project

'Many people criticise the participation of London and New York in the championship but when one travels to either Ruislip or Gaelic Park you will meet thousands of Roscommon people in these places who will turn up to the matches as they never get to see their team play at home.'

- Frank Dennehy, b. 1944

©GAA Oral History Project

Read a sample of a full length questionnaire: Mary Moran-Regan, b. 1965

Sligo concede a goal from Mayo's Padraig Carney during an inter-county match c.1950s ©GAA Oral History Project