Across the disciplines

Infant malnutrition is a threat the world over, affecting all genders, races, and social statuses. Even those who survive are still at high risk for reduced physical and cognitive development, capacity to resist disease, and ability to carry out physical work, and study and progress in school.

But a project led by an interdisciplinary trio of Boston College researchers could help make a difference in the global struggle against infant malnutrition.

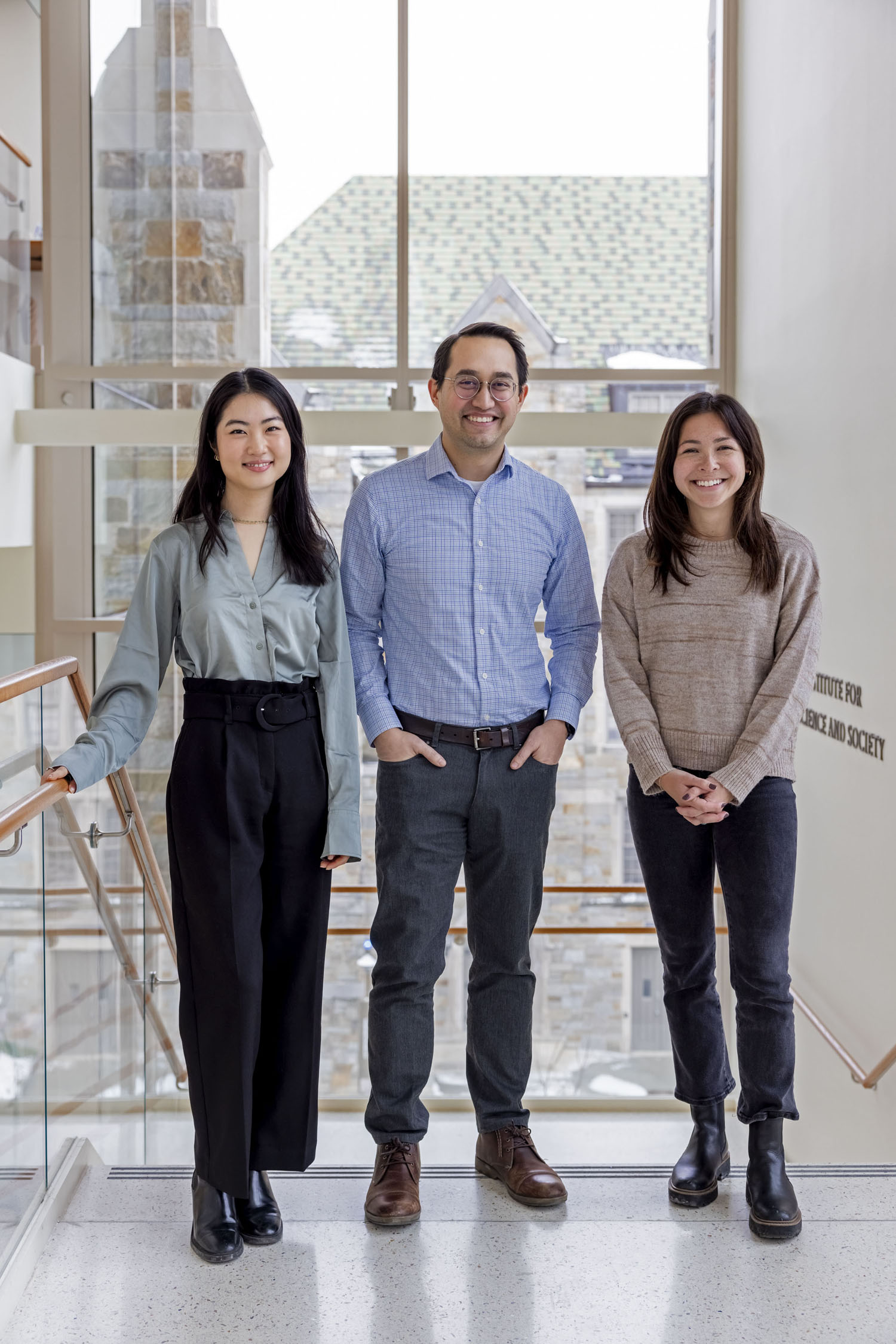

Assistant Professor of Engineering Bryan Ranger with Connell School of Nursing graduate students Jini Kim and Marisa Albert. (Caitlin Cunningham)

Supported by a grant from the BC Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society, Assistant Professor of Engineering Bryan Ranger, Assistant Professor of Computer Science Donglai Wei, and Connell School of Nursing Associate Professor Jinhee Park are conducting a pilot study in which frontline health care workers utilize a portable ultrasound scanner to collect images of muscle and fat distributions on infants suffering from malnutrition.

The goal of the project is to develop artificial intelligence to interpret this data as it relates to nutritional status and ultimately assist with clinical decision making. The BC faculty members are collaborating with investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and Jimma University in Ethiopia.

Last fall, Ranger received an Award for Inclusion Research from Google, which supports academic research in computing and technology that addresses the needs of historically marginalized groups globally; the award will fund broader ongoing work on AI-enabled portable ultrasound for health care workers in Ethiopia.

A major obstacle in dealing with malnutrition cases—especially in poor, low-resourced areas—is the lack of data that can provide a fuller evaluation of a patient’s condition, note the researchers.

“Nutritional screening tools cannot be reproduced adequately, nor do they show agreement with one another, or validity in identifying malnutrition,” explained Ranger. “Although one can use scales and tape measures to obtain anthropometric indicators such as weight, height, and body mass index (BMI), these do not effectively provide a comprehensive assessment of healthy growth and development. More advanced methods are expensive and only available in specialized facilities.”

Low-cost ultrasound technology and devices are available on the market, but require expertise to use, he said: “You can’t just give them to a health care professional in a low-resourced area and expect to solve the problem.” A scanner attached to a tablet and enhanced by AI, however, can help workers—with some initial instruction—in interpreting the data collected from patients.

Connell School of Nursing Associate Professor Jinhee Park (Lee Pellegrini)

“I believe Bryan’s work will address critical issues by creating a low-cost, portable assessment tool that provides an accurate and comprehensive child’s growth and nutritional status,” said Park. “If successful, this tool would help frontline health care providers to identify and treat malnutrition in infants and children, particularly in low-income communities.”

Last summer, Ranger, Connell School graduate students Marisa Albert and Jini Kim, and junior engineering major Hayoung Cho spent time at Jimma University, observing and training local health care workers to use the portable scanners as part of the pilot study. Jimma was selected for the project because it has a well-established nutritional research program and is one of the few sites in Africa that has the specialized equipment to take nutritional data, said Ranger.

“This is where the ‘inclusion’ aspect of the Google grant is relevant,” he said. “We want to be inclusive about the data we’re collecting. Developing a tool in Boston and then deploying it somewhere completely different doesn’t make sense. Our research collaborators at Jimma bring a valuable perspective and needed expertise to the project.”

The merits of interdisciplinary collaboration are apparent in this joint venture. Ranger, who earned a doctorate in medical engineering and medical physics through the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology as a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, brought a strong background in global health to BC from working with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. But he felt that insights from other fields would help realize this new utilization of portable ultrasound scanners.

A conversation with Connell School Dean Katherine Gregory—Ranger has a courtesy appointment at CSON—led him to contact Park, an expert in neonatal nursing whose research focuses on health and developmental outcomes of infants and young children with feeding problems as well as those of their families. He also got in touch with Wei, who studies the interplay between biological sciences and computer vision and is experienced in building computational models for biomedical image analysis.

“Coming to BC, and helping build a new department, has been a great experience,” said Ranger, one of the first faculty hires in BC’s Human-Centered Engineering program. “In addition to the interdisciplinary aspects of the program, I was drawn to the emphasis on a human-centered approach to solving global health challenges. I really value the opportunity to work with people who see the possibilities in putting knowledge and skills together, even if they come from seemingly disparate areas.”

Park said it is “a privilege” to be part of the team and share her acumen as a nurse “while developing a tool that has the potential to solve the many challenges we face. Interdisciplinary collaborations allow us to leverage the expertise of different professions to address health care challenges. As part of the largest group of health care providers in the country, nurses use more medical devices than any other health care professional and can provide unique insight on developing and designing medical products.”

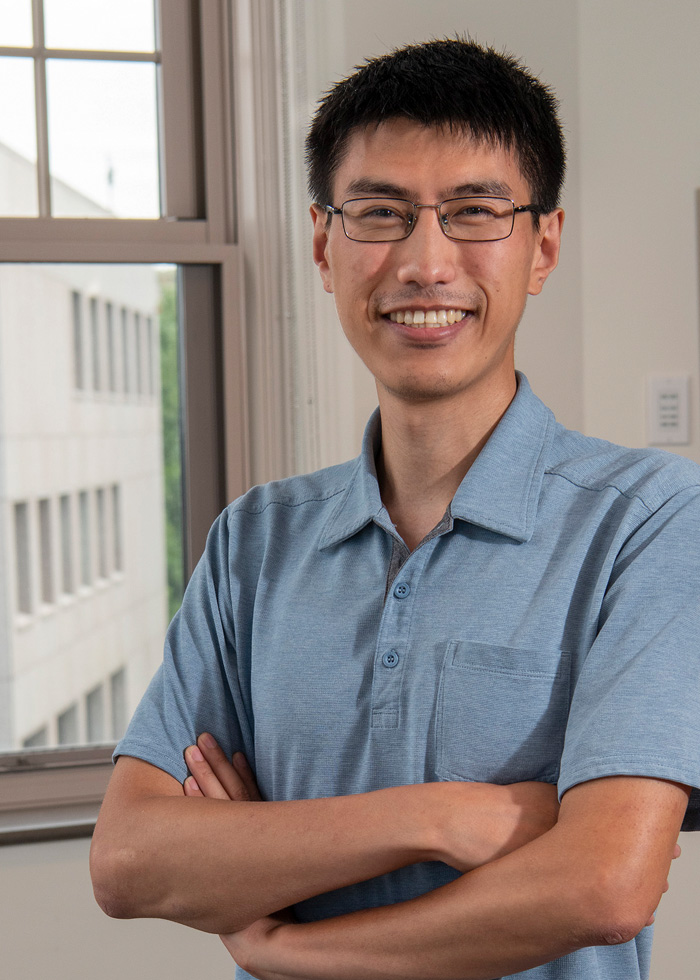

Assistant Professor of Computer Science Donglai Wei (Lee Pellegrini)

Wei, whose research lies in the domain of “AI for science,” has published works with biologists, clinicians, mechanical engineers, and civil engineers. “What appeals to me about interdisciplinary collaborations most is making a real-world impact with AI technology and the opportunities to formulate new problems for the AI field to solve.”

Albert and Kim appreciated the chance to be involved in the development of cutting-edge research, and to get a first-hand look at health care in a setting vastly different from those in which they’d worked.

“Not only did we have the opportunity to provide educational sessions of the ultrasound technology to the staff there, but we also had the chance to spend time in the hospital setting,” said Albert. “There are not enough words to express how much health care needs exist and it was a challenge to see things and know there is so much more that needs to be done beyond the scope of our work.”

Kim said, “This project serves as an exemplary illustration of how technology can be leveraged to provide more equitable and preventative care to patients, potentially fostering long-term impacts in health care. We not only identify implications for future studies but also recognize potential gaps that we can address throughout the course of the study. This helps refine the best interventional techniques for optimal result measurements when collecting different body components.”

Cho said her most vivid memories of the visit to Jimma include accompanying a nurse to observe patients; the sight of young mothers, families, and slim children in small, crowded rooms; and walls that displayed the number of children who had died each day (“I watched as the weekly and monthly count increased”).

“These experiences fueled my hunger to devote my purpose to continuing research on advancing affordable, standardized early detection and diagnostic tools,” she said.