Punch Lines

Rising comedy star Joyelle Nicole Johnson ’03 shares a few favorite laughs.

Goodfellas film still: Licensed by Warner Bros. Discovery. All Rights Reserved.

“Don’t Give Me the Babe in the Woods Routine”

As a crusading federal prosecutor, Edward McDonald ’68 sent some of the country’s most notorious mafia leaders to prison. But what he’ll always be known for is playing himself in the classic Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas.

One day in the spring of 1989, Edward McDonald ’68 received a phone call from the noted crime journalist Nicholas Pileggi. The two men had known each other for nearly a decade, ever since Pileggi first chronicled the courtroom exploits of McDonald, a swaggering federal prosecutor who’d won convictions against some of the nation’s most notorious mafia members. “Ed,” Pileggi said into the phone, “my friend Marty Scorsese wants to send a staff person down to take pictures of your office.”

Pileggi explained that Scorsese, the celebrated film director, was shooting his latest movie, an adaptation of Pileggi’s bestselling and wildly entertaining book Wiseguy, which traces the life of a mid-level associate in the Lucchese crime family named Henry Hill. McDonald, the prosecutor who’d secured Hill’s cooperation in government cases against higher-ups in the Lucchese family, had featured prominently in Pileggi’s book, and now Scorsese wanted to include him in his new movie, too. Pileggi told McDonald that the photos of his office would help Scorsese plan his character’s scene. “They want to make the set look authentic,” he said.

A few days later, a Scorsese staffer named Robin Standefer showed up at the Brooklyn offices of the Organized Crime Strike Force for the Eastern District of New York, where McDonald was attorney-in-charge. “So she’s taking a bunch of pictures in my office and asking me questions,” McDonald recalled when I met with him last fall. As Standefer was finishing up, McDonald turned to her. “Who’s playing me in the movie?” he asked.

“We haven’t cast that part yet,” she replied.

“I’ll do it! I’ll play myself!”

An hour and a half later, McDonald got another call from Pileggi. This time he’d pulled Scorsese into the conversation. “Robin came back here and told us you’re interested in playing yourself,” Pileggi said. “You want to have a screen test?”

In his nearly seventeen years as a prosecutor, McDonald obtained the convictions of an astonishing array of criminals, among them organized crime leaders; the inside man in the famed Lufthansa heist, which in its day was the largest cash robbery in American history; and numerous corrupt politicians, including the disgraced Senator Harrison Williams of New Jersey, who accepted bribes during the wide-ranging Abscam sting operation. But what McDonald will forever be remembered for is the few minutes he spent on screen in Scorsese’s movie, Goodfellas.

After talking his way into the part, McDonald went on to deliver a cracking performance, so comfortable and projecting such authority in front of the camera that people are always surprised when they learn he’s the actual guy he’s playing, and not a professional actor. In the scene, McDonald meets with Hill and his wife Karen, portrayed by Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco, to convince them to enter the witness protection program in exchange for Henry’s testimony against his former friends in the mafia. As they grow increasingly frantic, McDonald remains chillingly calm, nearly menacing, while laying out for them that cooperating with the government is their only chance for survival. Then, when Karen protests that she doesn’t know anything that would make her useful to the prosecution, McDonald delivers a line for the ages, one he made up on the spot. Leaning forward in his chair, elbows on his thighs, he scoffs, “Don’t give me the babe in the woods routine, Karen. I’ve listened to those wiretaps. And I’ve heard you on the telephone. You’re talking about cocaine.”

Three and a half decades after the movie’s release, strangers still excitedly recognize McDonald. “I’ll see people in the street or in a bar,” he said, “and they’ll say it: Hey, don’t give me the babe in the woods routine!”

McDonald photographed in his office, which is filled with mementos from his days as a crusading federal prosecutor and his star turn in Goodfellas.

Photo: James Farrell

Released in 1990, Goodfellas today is properly recognized as a masterpiece. As acclaimed for its acting and dialogue as its cinematography and directing, the movie is included on many lists of cinema’s greatest works. The American Film Institute, for example, ranks it as the ninety-fourth best American movie ever made (which, in my rather biased estimation, is preposterously low). But as Ed McDonald approached the Warner Bros. offices on Fifty-First Street in Manhattan a couple of weeks after his call with Pileggi and Scorsese, the last thing on his mind was where the movie he was about to audition for might wind up in film history. This is ridiculous! he kept telling himself. I’m not an actor. What am I doing?

McDonald may not have been an actor, but at age forty-two, his career was certainly reading like something out of a movie script. In 1977, six years after graduating from Georgetown Law, and following a stint with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, he’d joined the Organized Crime Strike Force, a squad of federal prosecutors established in the late sixties to combat mafia racketeering. In 1982, he became chief of the force’s Eastern District office, overseeing thirteen lawyers. He’d get up in the morning and race to learn what had been captured overnight on the bugs planted in mafia hangouts, or who undercover FBI agents had talked to. There were current trials to monitor and upcoming ones to prepare for, meetings with law enforcement agents working cases, grand jury appearances, verdicts being delivered. And, of course, there was the whirlwind coverage in the New York press. From morning to night, the job sizzled with excitement.

Odd, then, that a prosecutor who’d been part of the convictions of such major underworld figures as Colombo crime family underboss Alphonse “Allie Boy” Persico, Bonanno crime family boss Philip Rastelli and acting boss Joey Massino, and Lucchese family heavyweights Paul Vario and Jimmy Burke was poised to land a role in a Martin Scorsese movie not because of those cases, but because of his work with the distinctly small-time Henry Hill. But what made Hill interesting to a writer like Pileggi was the same thing that made him valuable to a prosecutor like McDonald: Vario and Burke, who inspired the Goodfellas characters Paulie Cicero and Jimmy Conway, adored him. They’d never trust him with any important jobs, but he was fun and charming and they loved having him around—which meant he knew everything about all the various crimes they were committing.

Now McDonald was about to screen test for Scorsese’s movie about that life, and he was feeling anxious. When he arrived at the Warner Bros. offices, the scene he encountered did little to relax his nerves. “It was bedlam,” he recalled. “Every guy with a small part—every waiter and every wiseguy—they were all jammed in there, coming in for their auditions.” McDonald made his way through the sea of hopefuls and entered a small room. There, sitting behind a desk, was Scorsese himself. McDonald hadn’t expected him. “I was really nervous,” he recalled.

Suddenly, the director leapt to his feet. “Oh, Mr. Prosecutor,” he cried, “I didn’t do nothing! I didn’t do nothing!” Then he started laughing.

The startling outburst had its intended effect. “He was trying to make me feel at ease,” McDonald recalled. “So I say to him, ‘You’re nothing but a mook!’”

“I’m a mook?” Scorsese shot back. “What’s a mook? You’re a mook!”

The two men laughed at their reenactment of the classic pool-hall scene from Scorsese’s 1973 film Mean Streets. “Okay,” the director said. “Let’s get to work.”

McDonald began to dutifully recite his lines from the script. After a minute or so, he began to panic. This is a joke, he thought to himself. It’s just horrendous. I’m so bad.

“Give me that,” Scorsese barked, grabbing the papers from McDonald’s hands and throwing them on the floor. He turned to the actors playing Henry and Karen for the audition. “He’s the prosecutor,” Scorsese told them. “Ask him questions.” For the next several minutes, they fired impromptu queries at McDonald, who was much more comfortable answering in his own words.

“Alright, stop,” Scorsese said. “That was great. You’ll be hearing from us.”

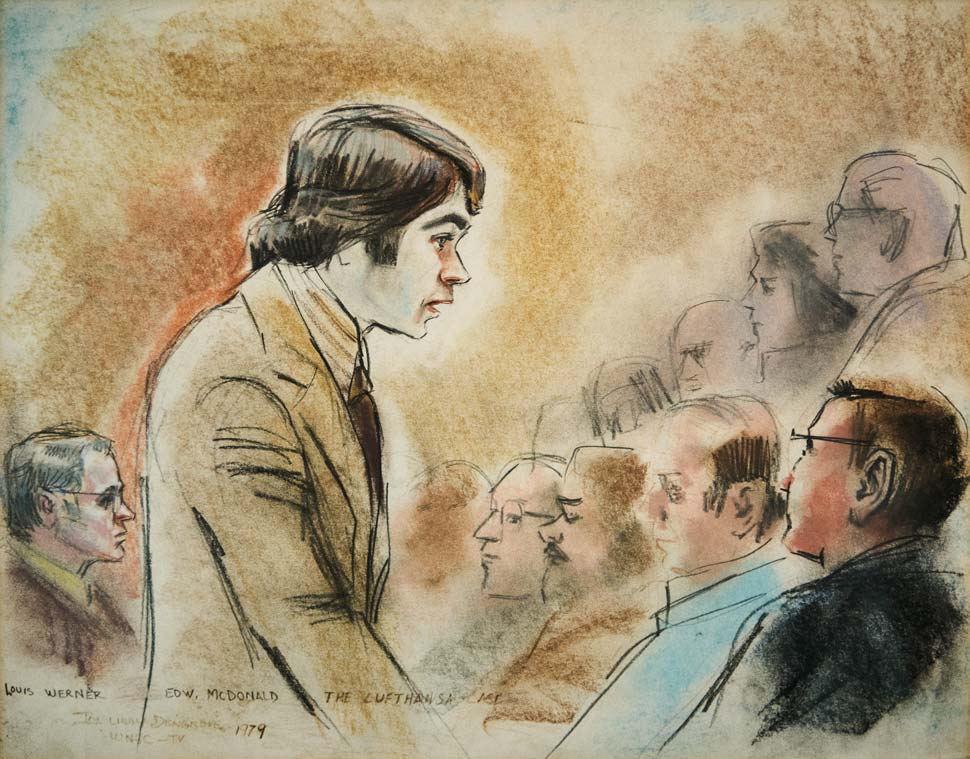

A courtroom sketch of McDonald’s 1979 prosecution of Louis Werner, the “inside man” in the Lufthansa heist, in which nearly $6 million in cash and jewelry was stolen, then the largest cash robbery in American history. Courtesy of Edward McDonald

If you’re a man of a certain age, there’s a good chance you’ve seen Goodfellas enough times that “Don’t give me the babe in the woods routine” is just one of many lines from it that you can quote. “Women never come up to me and recognize me,” McDonald told me with a laugh, “it’s always guys.” A lot of women like Goodfellas, actually, but with its violent and crude depiction of a violent and crude world, McDonald is probably correct that it appeals more typically to men.

In any case, Goodfellas is, without question, my favorite movie. So imagine my excitement when, not so long ago, I finally read Pileggi’s Wiseguy and discovered that McDonald went to Boston College. I knew right away that I wanted to write about him…but what were the chances that the stern, aggressive, all-business prosecutor I’d been watching on my television screen for the past thirty years would be interested in something as frivolous as a magazine article? I sent him an email to find out.

Fifteen minutes later, McDonald called me. “Of course I’m interested!” he bellowed. “Who wouldn’t want to be in a magazine? I’m a lawyer and an actor—that means I’ve got a big ego!” He laughed warmly and was self-deprecating throughout our conversation. I learned that he’d grown up in the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn and attended Xaverian High School before matriculating to BC in 1964. He played briefly on the basketball team as a freshman and majored in history, and it was on the Heights that he met his wife, Mary McDonald, who is from the Boston area and graduated from the nursing school in 1969. They remain happily married to this day and have three adult children.

A couple of weeks later, I visited McDonald in the Manhattan offices of Dechert LLP, the enormous international law firm where he’s practiced since 2003. He greeted me in a reception area on the twenty-eighth floor, casual in black jeans, sneakers, and a pink dress shirt. As we shook hands, I saw that the dark hair and lean frame of his Goodfellas days had made a few concessions to time, but he was tall and charismatic as ever.

He led me to the office where, at seventy-eight, he still works a couple of days a week, handling cases involving powerful corporations and Master of the Universe types. The walls of his office were filled with photos and mementos from his years as a prosecutor, including a Goodfellas poster (with a still from McDonald’s scene tucked into the frame), courtroom sketches from his notable trials, and a framed copy of a 1983 New York Magazine cover story called “Gangbusters” that Pileggi wrote about the Brooklyn Strike Force’s mafia prosecutions.

McDonald took a seat at his desk, the large windows behind him affording a sweeping view of Midtown Manhattan. He said that he’s at work on a book about his many cases. An entire chapter details his long, complicated, and often amusing relationship with Henry Hill, who died in 2012. “Henry was not Ray Liotta,” he said. “He was not a particularly bright guy. But he was as charming as hell.” The two men first met in 1980, and Hill served as an effective witness until the mid-eighties, when he was arrested in Seattle on a major drug case. McDonald helped him get probation, but Hill was continually getting into trouble. “I got him out of jail a lot,” McDonald said. “I was constantly going to bat for him. When the bars would shut down, he’d want to keep drinking so he’d break into a grocery store. They’d catch him sitting there drinking beer on the floor. He was a pathetic addict.”

McDonald and his team of prosecutors at the Organized Crime Strike Force for the Eastern District of New York. The group was photographed for a 1983 New York Magazine cover story. Courtesy of Edward McDonald

When I asked McDonald what it was like to film his Goodfellas scene, he pointed out something I’d never noticed in all my viewings of the movie. He’s actually in two scenes—the famous one in his office, and the one in the courtroom that follows. That’s him questioning Ray Liotta’s Henry. The scenes were shot over two days, he said, in a Social Security Administration building in Queens. Unbeknownst to McDonald, Scorsese had another actor in the building in case McDonald’s takes—six in all—didn’t work out.I asked McDonald about the remarkably enduring appeal of his performance, which, after all, amounted to a cameo. “Well, it’s a cameo,” he said, “except it’s the seventh-most lines in the movie.” That couldn’t be right, I replied. He’s onscreen for only a couple of minutes. “A lot of characters are in the movie a lot but they don’t speak very much,” he said. “I think it’s the seventh-most lines in the movie, because I have the screenplay…oh, and I counted one time like an idiot.” He laughed deeply.

McDonald, who has his Screen Actor’s Guild card to this day, managed to land a few other roles after Goodfellas. He played a prosecutor in a 1995 thriller called Kiss of Death. “I had a few scenes with David Caruso,” he said. “Stanley Tucci was in my scene. All these big stars were in the movie but it went nowhere.” He got another part, once again playing a lawyer, in a TV show called Michael Hayes that also starred Caruso. They spent an entire afternoon filming with lots of impromptu dialogue. “When it aired, what happens?” McDonald said. “My client turns to me and says, ‘Should I cooperate?’ I nod my head, yes. And that’s it.” A final role was arranged by a former mafia member named Sal Polisi, who’d been a cooperating witness for McDonald. Years later, Polisi wrote a screenplay about his time owning a social club with the former mob boss John Gotti. McDonald got a few scenes in the 2010 movie as a priest with a gambling problem. “It was going to be called The Sinatra Club, McDonald said, “but it went straight to video and they realized people go alphabetically when they decide what to watch so they changed the name to At the Sinatra Club.”

His acting career may have stalled, but McDonald said he’s proud and more than satisfied to have been part of Goodfellas. “I guess we have my obituary: He appeared in Goodfellas,” he said. “People are always coming up to me. It’s crazy. It’s like a cult movie. I mean, this is thirty-five years ago I shot the movie. It’s just a phenomenon. My oldest son went to Brown, and we were sitting in a restaurant up in Providence. And at a nearby table there were these young guys. We look over and one of them is going, ‘Don’t give me the babe in the woods routine!’” ◽