Men’s Hockey Soars

Head Coach Greg Brown ’90 led the Eagles all the way to the NCAA title game this season.

Photo: Beowulf Sheehan

BOOKS

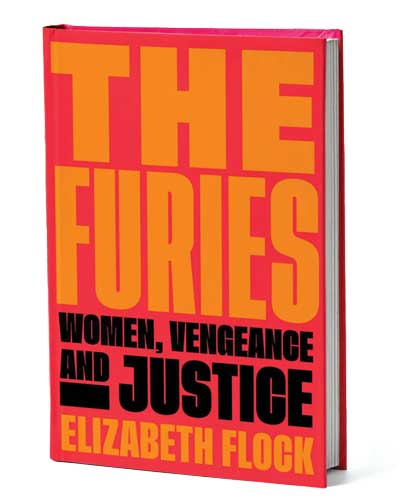

The Furies

Journalist Elizabeth Flock ’08 digs deep into what happens when women use violence to defend themselves.

When the journalist Elizabeth Flock ’08 was still a student at Boston College, she was sexually assaulted while on a trip to Rome with friends. Intimidated by the thought of having to relive the attack while testifying during a criminal case, she chose not to report the crime. But as the years passed, she was haunted by the question of what would have happened if she’d reacted differently during the assault itself. More than a decade later, she started searching for stories of women across the globe who had responded to violence with violence. She wanted to know what happened to them after they used violence to defend themselves. The result is The Furies: Women, Vengeance, and Justice, a meticulously reported examination of what happened when three women fought back against their abusers. The book received substantial coverage in the New York Times and the New Yorker, which had previously published some of Flock’s preliminary reporting that led to it. The Washington Post, meanwhile, praised Flock for withholding judgment about her subjects, finding that “her work is richer and more troubling because of it.” We recently sat down with Flock to discuss her new book.

You write of the agonizing process of deciding whether to report your own sexual assault. What factors influenced your decision not to report it?

I didn’t report my sexual assault to the Italian police because I could imagine what would happen. I thought I would just re-traumatize myself and potentially go through a really horrifying trial.

One study found that women who claimed at trial that they’d used violence only in self-defense were twice as likely as men to be convicted of crimes. The disparity was even starker for women of color.

The systems are built against women. The criminal justice system is so broken in so many ways. And I think women know deep down that if they fight back, they’re up against that. And then if you do fight back, you’re criminalized for it. That’s what the research shows. Overwhelmingly, women take plea deals and go to prison after fighting back against abusers.

The women in your book come from very disparate backgrounds. One killed her rapist in Alabama, another was a freedom fighter in Syria, and another organized a gang to violently respond to domestic violence in India. Given that so few women fight back, what led your subjects to make a different choice?

They all told me similar things: “I just didn’t want to die. I just wanted to protect myself or my community.” Yes, they’re very different, but they are living in the same kinds of challenging scenarios, and they’re doubly vulnerable. They’re women and they’re poor in Alabama and can’t afford better legal representation. Or they’re poor and they’re Kurdish, a people who have been oppressed for generations. Or they’re poor and they’re low-caste, and so they don’t get justice for multiple reasons. Women who fight back in many cases are women who have nothing to lose.

All of the women you write about start to make choices that complicate the morality of their narratives. For instance, Brittany, the woman in Alabama, was arrested for arson while still on trial for murder.

In my own story, I was passive, and I wanted to understand what it looked like when women were more active. But of course, as any good journalist knows, the longer you follow something, the more complex it gets. With all vigilantes, there’s a moment where you’re cheering them on and then all of a sudden you’re saying, “Hey, this might not be quite as clean as I thought.” For each of the narratives, there was a clear moment when things shifted. These are women who are fighting for justice, and they are also really flawed humans like the rest of us, and the situations are really complex. That’s why it’s important to follow these things long-term, because if not, you’re just getting a snapshot.

There are abundant examples from fiction of women seeking violent revenge, like in the movie Kill Bill and the Greek epic Medea. What has made these stories so appealing through the centuries?

I think we’re drawn to these stories because we want to be them. It’s partly because so many women have experienced some kind of violation and wished that they fought back. Heroes interest us because they’re extraordinary people, but anti-heroes interest us because they’re extraordinary yet also complicated like all of us. You add in the layer of sexual or domestic abuse, and I think it’s no wonder that women are interested in these stories, whether it’s Kill Bill or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. It’s been an obsession of ours since the beginning of time, as far as I can tell. ◽