Documenting Giannis Antetokounmpo

In her new film, Kristen Lappas ’09 captures the life of one of the most famous athletes in the world. Here’s how she did it.

Photography by Caitlin Cunningham

Tracking Bigfoot

In his new book, BC journalism instructor John O’Connor ventures into the Northern California woods in search of an American monster.

A few years ago, John O’Connor was casting about for something to do. O’Connor is a successful travel writer who teaches part-time in the Boston College journalism program, but he describes himself as “underemployed” nonetheless. When he finally settled on his next project, it involved writing a screenplay for a movie about the mythical beast Bigfoot.

“It wound up as a very bad B-movie script—a kind of horror-adventure flick,” O’Connor recalled recently. “You know, Bigfoot rampaging through this enclave of environmentalists, and kind of this whole … I’ll spare you the details. But anyway, it sort of grew from that.”

The “it” in question here is O’Connor’s new book, The Secret History of Bigfoot: Field Notes on a North American Monster, which he ended up pursuing instead of a movie deal. Published earlier this year by Sourcebooks, it has received considerable attention, including reviews by NPR and the New York Times and Washington Post.

The book examines the history of the Bigfoot legend, of course, meticulously charting purported sightings, important dates and people, and regional variations on the seven-hundred-pound mammal (Florida, for instance, is said to be home to the Skunk Ape, a four-toed cousin of Bigfoot.) For all his documentation of the myth, however, O’Connor winds up being more interested in the people, known as Bigfooters, who pore over Bigfoot minutiae the way JFK-truthers do the Zapruder film. These are the people, men and middle-aged, for the most part, who excitedly tramp through woodlands in search of evidence of the monster’s existence.

So after more than a year of reporting, what can O’Connor tell us about whether Bigfoot is real? “The challenge of the book,” he said, “was to try not to put my foot down too firmly. There’s this kind of sweet spot of ambiguity. I didn’t want to prove or disprove that Bigfoot exists, but hopefully to remind people as much as possible to be rational, and to be guided by reason and fact-based science. But also to stay in contact with a kind of more enchanted view of the world.”

In the following excerpt from the book, O’Connor takes us into the California woods with a group of determined Bigfooters. —John Wolfson

Northern California? Some kinetic force had kept me away. Until now, at the tail end of my Bigfoot year. Coming down I-5, cresting a ridge, I gazed down a long gorge of pinyon-dotted hills. The land began teetering, the trees growing taller. Across upper-west California and southwestern Oregon, covering eleven million acres, runs the Klamath-Siskiyou wilderness. It contains some of our last truly ancient forests, making it a top contender for Squatchiest locale in the country.

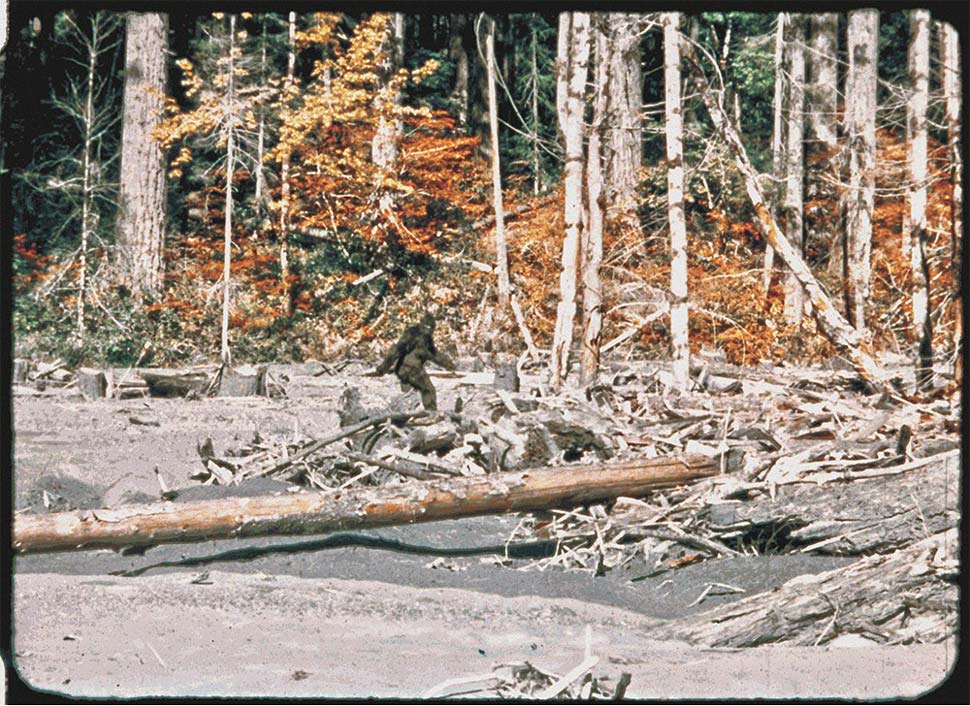

Turning off the highway, I was bluntly decanted into a maze of logging roads lightly dusted with pine needles. My target was Bluff Creek, a tributary of the Klamath River, in the Six Rivers National Forest. Fifty-four years ago, filmmakers Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin—if “filmmakers” is the noun we’re after; they’d rented a Cine-Kodak K-100 from a Yakima camera shop—recorded a Bigfoot walking through a clearing on the creek’s sprawling sandbar. You’ve seen the footage: a wobbly, sepia-toned fifty-nine seconds of a bearishly stout Bigfoot, darkly furred like an otter, throwing a sidelong glance over its shoulder and holding the camera’s gaze before striding purposefully away. Whatever it is, you can’t quite take your eyes off it. A prelapsarian Adam, or Eve, as it turned out (a close viewing reveals prominent breasts). The film is the single most infamous and contested piece of Bigfoot evidence in existence, with an audience divided between those who’ve dismissed it as a hoax and those who believe it has never been convincingly debunked. Patterson and Gimlin always stuck by it. (Patterson passed away in 1972 at age forty-six. Gimlin is in his nineties.) Their brilliance was in selling us the idea of Bigfoot convincingly enough to last for half a century.

If not for the Patterson-Gimlin film, chances are Bigfoot would’ve faded into history’s back pages, a dustbin relic no better known than the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary. From the Pattersonian stage, however, it trod audaciously into the American vernacular, embodying, in its homespun gigantism and subversive charm, the myth of America itself. Such is the talismanic regard for the film among Bigfooters that Bluff Creek has become something of a pilgrimage site, but only recently. The actual location was lost decades ago, misplaced at the foot of a troglodytic gulch. In 2011, a group of researchers calling themselves the Bluff Creek Project (BCP), referencing old sketches and photographs, located the unrecognizably overgrown site.

In the intervening years, the BCP has reshot the film several times to try to determine its veracity. Hamstrung by the fact that the celluloid “Patty,” as she’s known, is only about two millimeters tall and by the film’s poor quality, they’ll be the first to tell you they haven’t succeeded. After the promise of rediscovery, Bluff Creek relinquished a few clues. The film, however, remained dauntingly unknowable, its 954 frames occluded by a pestering question: Could Patty possibly be real? There’s more than the usual tension around the truth. Bigfooting’s guiding credo, it could be said, hangs in the balance. BCPer Robert Leiterman has this to say about Patterson and Gimlin’s legacy: “Either one of the most intriguing wildlife films of all time or the greatest hoax of a complicated century.”

All the same, the BCP illuminated an important pop-cultural moment at risk of falling into obsolescence. Wanting to see their work, I reached out. They kindly agreed to let me tag along on a shoot. From member Rowdy Kelley, I’d received a GPS pin to their Bluff Creek camp, where at last I came upon another vehicle, a sand-colored Dodge Ram, idling in a turnout. Inside, James “Bobo” Fay from Finding Bigfoot and Rowdy Kelley were chewing burritos with hot air blasting. They’d been waiting for me.

“Glad you made it,” Rowdy shouted from the passenger seat. “Any trouble?”

“Eh.”

We spiraled down a rutted lane to a berm roosted high above Bluff Creek. A few trucks were wedged around a four-corner farmer’s market tent. We warmed ourselves at a propane heater underneath. On cue, it began to rain. Rowdy, fifty-four, a film producer and location scout with a grizzled face like the actor Timothy Olyphant, sparked a camp stove for a round of hot chocolates. Daniel Perez, fifty-eight, an electrician who publishes a monthly newsletter, Bigfoot Times, and Robert Leiterman, sixty, a retired park ranger, introduced themselves. Daniel wore a gray hoodie, jeans, and a camo ball cap over shoulder-length black hair. Robert, in wire-rim glasses and fleece vest, leafed through a galley copy of his new book, The Bluff Creek Project: The Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot Film Site, a Journey of Rediscovery. All were from California and had been involved with the BCP in one way or another for years.

Bobo, though not officially of the group, had been to Bluff Creek a bunch and was instrumental in the film site’s rediscovery. He was much thinner and more rangy looking than on TV. His dark hair was cut short. His deep-set eyes glittered with intelligence and shyness, as if he understood something I did not and never would. He was sixty-one years old and well over six feet tall. Aside from Barackman, his Finding Bigfoot costar, perhaps no living Bigfooter has a reputation to compare with Bobo’s. Before it ended in 2018, the show ran for nine seasons and one hundred episodes, snaring 1.3 million weekly viewers and spawning two spin-offs (Finding Bigfoot: Further Evidence and Finding Bigfoot: Rejected Evidence), despite failing to make good on the promise of its title. It remains one of Animal Planet’s most-watched shows. Bobo couldn’t stay. He had somewhere to be. Before leaving, he loaned me a winter sleeping bag. I’d brought only my summer bag (“It’s California. How cold could it be?”).

In the morning, Robert, Daniel, Rowdy, and his dogs, Chloe, a fox-rat terrier, and Daisy, a Westie, tramped down to the film site. It was in a densely timbered wood of alder and maple. It bore little resemblance to the sun-washed glade in the original film. When Patterson and Gimlin visited in 1967, the place had been scoured by a flood. The BCP had cleared brush and saplings to return the site to a semblance of its former self, but it remained marked by time’s current. Obscurities lingered. Using measurements made in 1971 by Bigfooter René Dahinden, they set themselves the task of reconceptualizing the film site, laying out a surveying grid, remeasuring, and formulating ideas about what had happened here. “Trying to locate the landmarks through a fur coat in a lousy film is a losing proposition,” a skeptical David Daegling has written. But Daegling, author of Bigfoot Exposed: An Anthropologist Examines America’s Enduring Legend, had never been to Bluff Creek and had not seen the landmarks for himself. In fact, the BCP had located landmarks, or “artifacts,” as they called them—tree stumps, fallen logs, a big Douglas fir over Patty’s shoulder in frame 352, taking bore samples to assess their age—and confirmed some of Dahinden’s data, such as Patty’s approximate pathway and the distance, roughly, between her and Patterson (one hundred feet). In 2011, Gimlin came down to eyeball where he’d seen Patty slouching toward infamy all those years ago. It was about twenty feet off the BCP’s estimation.

Frame 352 from the famed Patterson-Gimlin film that allegedly shows Bigfoot in the wild. The film is the single most infamous and contested piece of evidence for the existence of the woodlands monster.

This afternoon, they were tinkering with camera lenses. Dahinden, who died in 2001, thought Patterson’s camera had a 25-milimeter lens. It’s a signal detail, Rowdy said. If you know the lens size plus focal length, aperture, and distance between the camera and subject, you can guesstimate the latter’s height with something called a field of view formula. Patty’s height has been reckoned at between six feet and seven feet three inches, but no one really knows. “If she’s six feet, it could very well be a man in a monkey suit,” Daniel explained. “But if she’s seven three, then the probability of a monkey suit radically diminishes because how many seven foot three people do you know?” Patty’s height, then, was indicative of the film’s plausibility. “Skeptics want Patty to be shorter so they can throw the whole film out,” said Daniel. The hope was, by reshooting with 15-, 20-, and 25-milimeter lenses, the BCP could, once and for all, settle the question of Patty’s height.

By most accounts, Roger Patterson was a con artist who struck on a Bigfoot “documentary” as a money-making scheme and roped in his pal Bob Gimlin to assist (they were scouting for tracks along Bluff Creek when they happened upon Patty, so the story goes). These are suppositions, but to skeptics, Patterson’s case doesn’t look great. The fallout commenced immediately. In 1968, Bigfooter Bernard Heuvelmans was among the first to declare the film a patent fraud, noting an odd likeness between it and an illustration for an old article in the pulp men’s magazine True (the illustrated Bigfoot also had breasts and threw an over-the-shoulder glance). British primatologist John R. Napier, otherwise sympathetic to Bigfooters, thought the biomechanics of Patty’s gait pointed to a hoax—“The creature shown in the film does not stand up well to functional analysis. There are too many inconsistencies.” Although he did admit he “could not see the zipper.” Daegling, after analyzing the film frame by frame with an expert in hominid locomotion, came to an analogous conclusion: “It is a testament to human ingenuity and mischief rather than to the presence of an undiscovered species.” It didn’t help matters when, in 2004, a costume maker named Philip Morris told writer Greg Long he’d sold a gorilla suit to Patterson for $435 shortly before the film came out. Or when Rick Baker, a special effects and makeup artist who created Harry in Harry and the Hendersons, said the Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot looked like it was made with “cheap, fake fur.” Or when a Pepsi bottler from Yakima, Bob Heironimus, claimed he’d been the one wearing the suit. Or when Bigfooters Cliff Crook and Chris Murphy, using computer enhancements, enlarged the film to reveal what appeared to be metal fasteners on Patty’s back. Even Robert Leiterman, in his Bluff Creek homage, concedes, “I’d rather it were otherwise, but the case for Bigfoot just isn’t looking strong to me these days.”

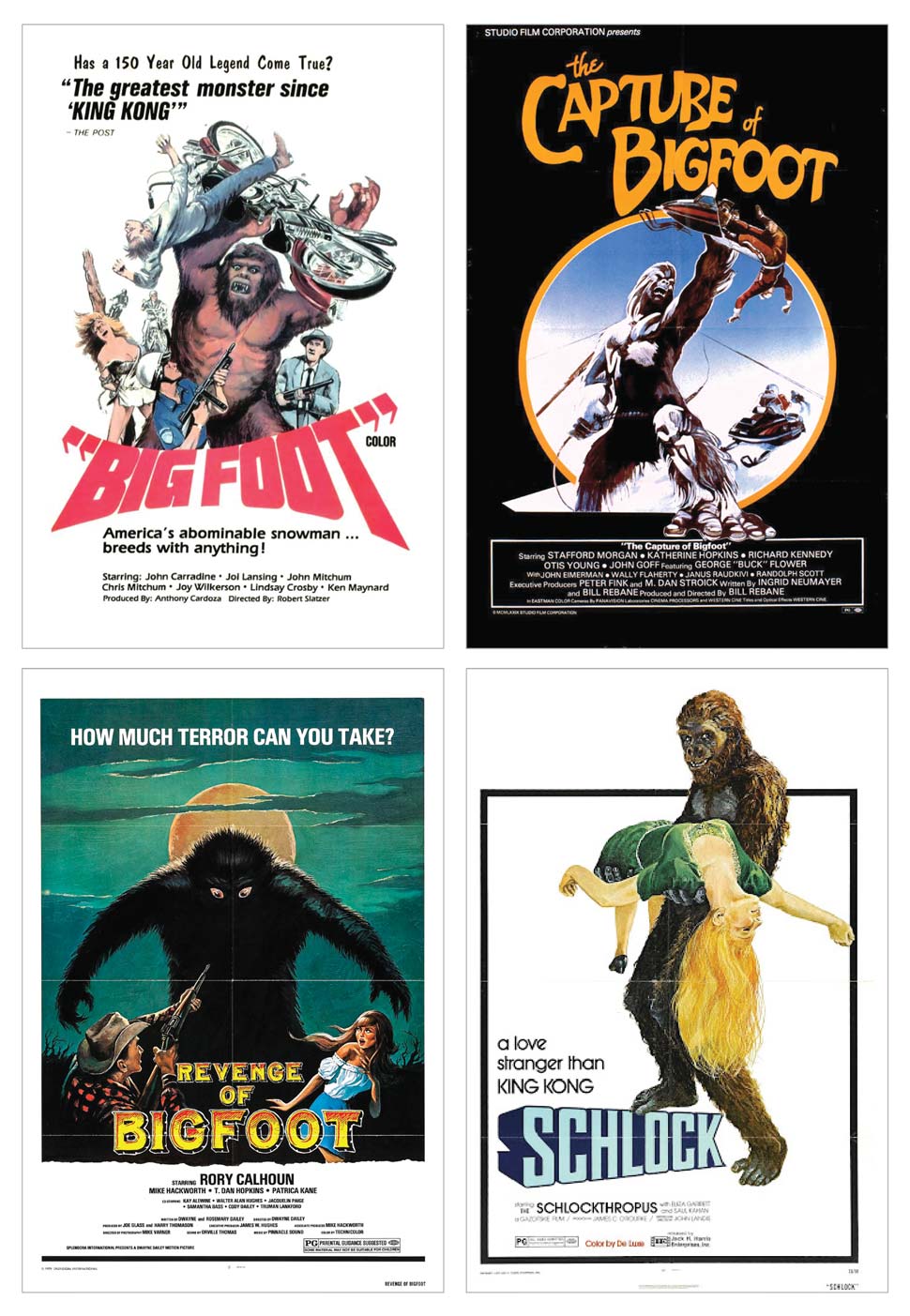

Bigfoot reached a cultural zenith in the seventies, captivating imaginations and inspiring several (forgettable) movies.

Admittedly, it’s hard to watch the film and not see a singing telegram. But enthusiasm for it has in no way dimmed. The anthropologist Jeffrey Meldrum, in Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science, mounts a vociferous refutation of the above. Not only do the gait biomechanics, musculature, and physical dimensions hold up to scientific scrutiny, he wrote, but the costume technology available to Patterson in 1967 couldn’t have fabricated a creature as sophisticated as Patty. Nor could it today, he claims. “Isn’t it curious that such a hypothetically skilled costume designer had never been employed in the Hollywood film history then or since?” For some Bigfooters, Meldrum’s word is enough.

The Bluff Creek Project tended to be more laid-back about the whole thing. They neither wanted to debunk the Patterson-Gimlin film nor make excuses for it but simply to account for how it’d been made. “I just focus on what I know,” Rowdy told me, “which is film.” It required a stubborn attentiveness to detail bordering on obsession, a near-Calvinist work ethic, and a stomach for truly terrible weather.

The guys had more to do. I puttered around, taking photos of the creek and film site. Bluff Creek was all but cut off from the outside world. Given time, it would return to its old stolidity, to its manifold uselessness. For now, it lay somewhere between pristine and cultivated, wild and tame. You can trace the etymology of “Bigfoot” to this tangle. Just upstream from us, on August 27, 1958, a cat skinner named Jerry Crew found sixteen-inch footprints in the dirt near his bulldozer on Bluff Creek Road, then being cleared for logging access. Other men at the worksite had seen similar tracks. After the Humboldt Times reported the story, the Associated Press picked it up: “Who is making the huge 16-inch tracks in the vicinity of Bluff Creek? Are the tracks a human hoax? Or, are they actual marks of a huge but harmless wild-man, traveling through the wilderness?” Crew referred to the print’s owner as “Big Foot.” They gradually petered out, along with the news coverage, but the name stuck.

A decade later, Patterson’s film fused Bigfoot into our perceptual milieu. The film’s success lies as much in its medium as in its timing. When it landed in theaters in 1968, packaged as a feature-length documentary, Bigfoot: America’s Abominable Snowman, moviegoing was experiencing a seismic shift away from small, urban movie houses to suburban multiplexes and rural drive-ins. That’s inadequate to describe a decade of white flight, exclusionary zoning laws, and quasi-legal segregation that left African American neighborhoods like Chicago’s South Shore in havoc. But suffice it to say that seven-hundred-seat suburban/rural theaters meant the Patterson-Gimlin film could be seen by millions of Americans.

In its wake came a flotsam of Bigfoot movies, both fictional and non, playing to predominantly white audiences. All but one were flesh-obsessed, bottom-feeder schlock of chartless, tsunamic stupidity, including Schlock! (1973), about a Bigfootesque serial killer who terrorizes a California suburb while falling for a witless blind girl with a heart of gold.

By the late ’60s and early ’70s, Bigfoot took on an increasingly starring role outside the multiplex too. No doubt emboldened by Patterson’s film, eyewitnesses, seeking validation and perhaps more, sprang forth from Florida glades, the Jersey Pine Barrens, Delta bottomland, the Colorado Plateau, Kentucky hollows, and Texan Hill Country, bearing both cogent and overcooked accounts. John Green, in his migratory treasury of sightings, Sasquatch: The Apes Among Us, claimed to have dug up fifteen hundred “confirmed” Bigfoot encounters in the United States prior to 1978, including a swollen nine-year sweep from ’68 to ’77. “Bigfoot was entering its halcyon days, the 1970s,” wrote Joshua Blu Buhs, “when it was an entertainment icon, object of ardent devotion, and subject of scientific inquiry.”

Before we left Bluff Creek, Robert shoveled clumps of dirt into sandwich bags for souvenirs, taking care to refill each divot he made. “You wouldn’t want a Bigfoot to twist its ankle,” he joked. We huffed back to camp, Rowdy and I carting a wheelbarrow of filmmaking tackle up and over the Sisyphean ground, every bend revealing a calamitous rock scree or miasmic worm ball of roots and mud.

At my car, I produced a six of Coors, ice-cold and glistening magnificently. I handed one to Rowdy. We toasted the day’s labor. “Very cool” was his verdict. I couldn’t have agreed more. With Bobo’s sleeping bag rolled out in my tent, the aches of the day subsiding, the roar of wind quieted by the trees, I didn’t want it to end. Even in my frozen-catatonic state, it was electrifying. In my notebook I scribbled: “I could stay out here a hundred nights." ◽