Jordan McGirk sits in his former studio in St. Louis. Courtesy photo.

The young man in the painting grips a beer can on a bright, summer day. He appears lost in his thoughts, unwilling to acknowledge that an off-white cloud, embedded with a skull, sits atop his head like an oversize hat.

The artist, Jordan McGirk, says the specter of calamity looms over this “summer bummer boy,” waiting to wreck his world. But he’s unwilling to act, happy to chill out. Content to sip his beer, brewed locally, and enjoy the beautiful day because big problems—climate change, gun violence, the spread of misinformation—are too hard to tackle.

This dichotomy, between solving problems and society’s collective inability to ditch apathy to confront these challenges, is the theme of McGirk’s latest exhibition, on display in Boston College’s Gallery 203 from November 8 to November 29. An opening reception for the exhibit, titled Good Weather, will take place on Wednesday from 6-8 p.m.

“We have a responsibility to engage in our lives and think of ourselves as participants, not just passers-by,” says McGirk, who serves as the administrative assistant to the dean at the School of Social Work when he’s not honing his craft as an artist. “Perhaps we need a little bit of horror in our lives to shake us out of our apathy.”

McGirk has used art to process his thoughts—to figure out how he feels about the world around him—since he was a kid. He grew up drawing all the time, he says, eschewing TV for pencils and scrap paper. His subjects ranged from space ships to dinosaurs.

Sometimes, his parents would find him in his room, talking to himself as he filled up pages upon pages of paper with intricate depictions of animals. “I think it was my way of coping with the world,” he says.

A young man grips a beer with a cloud sitting atop his head like a hat in McGirk’s Summer Bummer Boy.

McGirk didn’t pick up a paintbrush in earnest until college. He’s colorblind, he says, and felt self-conscious about color theory, the study of how colors work together and how they affect our emotions. But he had to pick a medium, and his professors at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he earned a B.F.A. in studio art in 2009, persuaded him to choose paint.

“Painting is a fat material that goes on almost like layers of skin,” says McGirk. “It’s this thing you can kind of tug and pull and make behave in interesting ways.”

Over the past 13 years, he has exhibited work nationwide, from the Amos Eno Gallery in New York to the AVC Art Gallery in California. He is currently displaying pieces from his Good Weather series at the Houska Gallery in Missouri.

McGirk drew inspiration for his new paintings from some of his favorite things—comic books, heavy metal music, and video games. He says the mood of the work was shaped in part by Elden Ring, a role-playing game whose story was crafted by popular novelist George R.R. Martin.

“It’s so overwhelmed by moodiness,” he says of the game. “Every progression you make is also built on something more terrible coming later.”

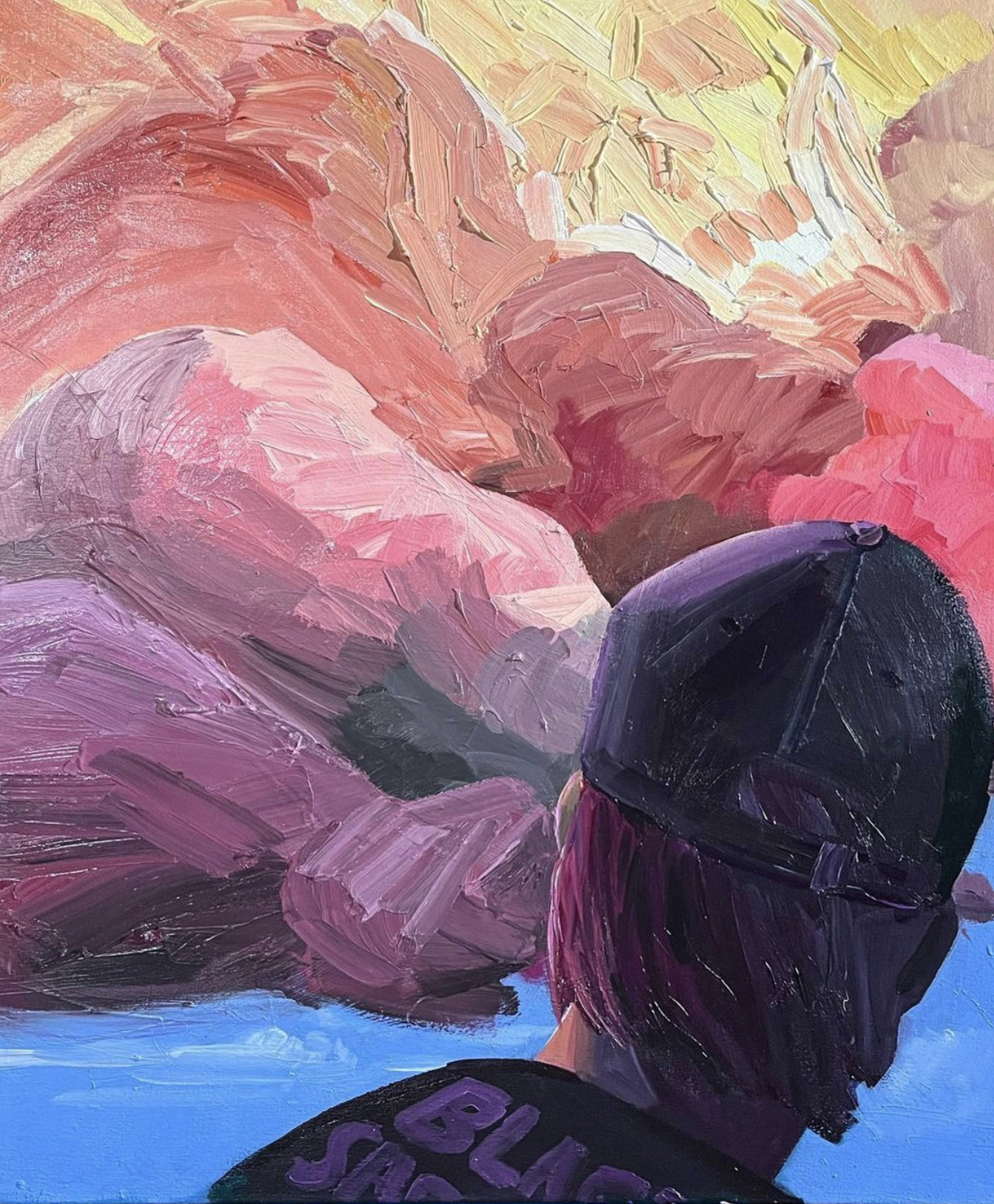

The colors he uses—bright blues, yellows, reds, greens, and purples—betray a creeping sense of dread. That’s Pretty Bleak, for example, depicts a Black Sabbath fan with purple hair gazing at a tangle of clouds that camouflage a yellow skull.

McGirk, who earned an M.F.A. in visual art from Washington University in St. Louis in 2011, says that artists typically use bright colors to invoke joy and happiness. He uses them to make it easier to confront difficult issues head on.

“It’s a way of drawing viewers in to talk about difficult subjects,” says McGirk, who created all 13 paintings for the exhibit in his home studio in Southborough, Massachusetts. “It’s an attractive way to talk about hard things.”

A Black Sabbath fan with purple hair gazes at a tangle of clouds that camouflage a yellow skull in McGirk’s That’s Pretty Bleak.

He started working on these paintings, mostly oil and acrylic on canvas, during the height of COVID-19. At the time, he noticed that a lot of popular publications had begun to use apocalyptic language to describe the state of society, and he started to wonder whether it’s possible to feel simultaneously hopeful and cynical during a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

“I wanted to wrestle with what it felt like when things feel like they’re ending and they’re far too big,” he says. “I felt like it was good to explore the paradox of how you confront those things—with hope or despair.”

McGirk’s position is that complacency leads to trouble, increasing the likelihood of cataclysmic disaster. He points to climate change as a prime example of a problem that we need to address now, before it gets worse.

“If we sit on our hands, it undoes us while we’re watching TV,” he says. “It’s happening whether we want it to happen or not.”

McGirk draws parallels between his painting and social work. Like a social worker, he says he feels responsible for confronting big, messy problems to make the world a better place.

“The enterprise of engaging and getting messy and dirty and listening closely to calls for help—that’s something that I really relate to in my work,” he says. “It’s about hearing those calls and taking them seriously.”