At a time when gloomy assessments about the state of the world and the U.S. economy appear to be spreading, a marquis collection of leaders and experts rang some bells of optimism at Boston College, while calling attention to troubling uncertainties as well as opportunities ahead for investors, companies, and the general public.

Watch The Videos

Missed the conference? Watch the video replays of each speaker now.

The conversations took place at the Carroll School of Management’s 15th annual Finance Conference. Returning to its in-person format this year, the all-day event on May 6 brought together Boston College alumni and others active in the financial services industry. They heard and posed questions to a Nobel Prize-winning economist, a former U.S. secretary of defense, a former White House economic czar, a celebrated investment adviser, and a rising Carroll School scholar.

The conference began on a high note with Paul Romer, who won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for documenting the ways in which ideas propel innovation and growth. He prefaced his remarks with kudos to Boston College and the Carroll School for holding an annual conference that draws on these very themes, noting that John and Linda Powers Family Dean Andy Boynton, co-author of the 2011 book The Idea Hunter, “understood the power of ideas early on.”

Paul Romer, recipient of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

Commenting on the current mood in America, Romer noted that he hasn’t seen so much pessimism since his days as a graduate student in the 1970s, when inflation and oil shocks were roiling the economy, as they are now, once again. And yet, through history people have found ideas “that give us so many ways to do more with less,” he said, rattling off a list of seemingly small notions that have unexpectedly solved huge problems. These include the idea of dissolving a few inexpensive minerals and a little sugar in water, which in recent decades has saved countless lives in the developing world by rehydrating children who had life-threatening diarrhea.

Andy Boynton, ’78, P’13, John and Linda Powers Family Dean, Carroll School of Management

“It’s not even remotely possible that we’ve run out of new things to discover,” said Romer, a New York University professor who delivered the Dorothy Rose Knight Economic Keynote address.

He added that ideas have far-reaching effects essentially because they’re replicable—once discovered, the idea of rehydration therapy could be used to save children over and over. Romer also gave a shout-out to government, which is needed to help set the legal framework of innovation and “make sure that the ideas are shared” through required public disclosures.

Is inflation on the way out?

One source of hand-wringing at the moment is the return of high inflation—a predicament that occupied most of a session featuring Christina Romer (no relation to Paul), who served as chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama.

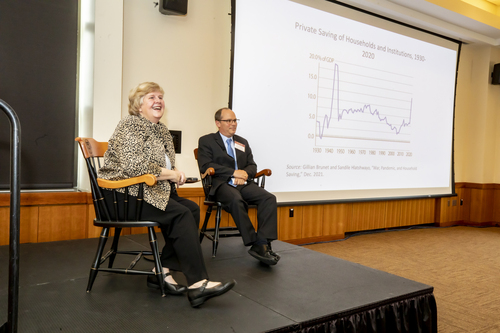

Christina Romer, Chair, Council of Economic Advisers (2009-2010), and Philip Strahan, Professor of Finance, Carroll School of Management

In a conversation with Professor Philip Strahan—two scholars, seated on a stage in the elongated Murray Room in the Yawkey Athletics Center—Romer pointed a finger at the outsized stimulus packages enacted during the pandemic that have apparently over-stimulated the economy, spurring inflation.

“Unemployment insurance is what you’d want in a pandemic. What was wrong is that we did too much,” Romer said of the stimulus. That, along with Americans making up for lost time with consumer purchases, deepened supply-chain woes. All that made for a classic inflationary case of too many dollars chasing too few goods, or “too much demand chasing after not enough output,” as the economist put it.

Now a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Romer was confident that the Federal Reserve will be able to tame inflation as it calms down a hyperactive economy. That was welcome news for an audience of 125 professionals in the financial industry (along with academics and others), who sat at banquet tables in the Murray Room and spoke up during Q&A segments.

Related

Hear from alumni and students who attended the 15th annual Finance Conference

At the same time, Romer said we should expect a little pain along the way. Her “best guess” is that the anti-inflation medicine dispensed by the Fed will prompt what she termed a “short, mild recession.” And yes, there might even be a transitory period of “stagflation,” Romer said in response to a question from a young woman who wouldn’t have a firsthand memory of the last time there was simultaneous inflation and stagnation (high prices and slow growth with relatively high unemployment), in the 1970s.

Strahan, the interlocutor—who holds the John L. Collins, S.J. Chair in Finance at the Carroll School—broached a question seldom discussed in polite company, or on the opinion pages of The Wall Street Journal. Might there be winners as well as losers as a result of inflation? Romer replied that indeed, the understanding through most of American history has been that inflation helps debtors (those making fixed payments on debts such as mortgages, with dollars that are worth less than before), but hurts creditors, who hold financial assets. She was quick to acknowledge that today, however, “People just hate inflation.”

Or should we go looking for “pro-inflation assets”?

As a much-listened-to investment advisor, Richard Bernstein is not prepared to bet on inflation ending any time soon, partly because of the supply chain issues that he thinks will have stubborn effects on markets and the economy (limiting the goods that the dollars are chasing after). Still, appearing virtually on a big screen at the otherwise in-person conference, Bernstein, who had come down with a mild case of COVID, underscored that there are “tremendous opportunities” for investors amid macro-economic shifts.

Richard Bernstein, Chief Executive Officer/Chief Investment Officer of Richard Bernstein Advisors LLC

In particular, the CEO and founder of Richard Bernstein Advisors LLC turned the audience’s attention to what he called “pro-inflation assets.” These would include energy, commodities, junk bonds, real estate, and natural resources, among other assets with longer-term earnings potential. Bernstein singled out the energy sector, which he said has long-term growth projections almost twice that of tech, even though it’s widely considered an old “boring” stock. He said, “The time to invest in things is when people don’t talk about it anymore.”

Nowhere near his favorite’s list of investments would be cryptocurrency. Boynton, who moderated the session, explained to the audience that Bernstein, who is prolific on Twitter, has “affectionately” referred to Bitcoin as “Bit-con.” Bernstein amplified the point, calling crypto “the first truly global financial bubble—the biggest in history.”

Is the West winning?

Geopolitical hotspots have always been a topic at the Finance Conference, because of the way international events can throw curves at markets and the entire economy—as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shown. Helping the audience make sense of this crisis and other geopolitical developments was Ash Carter, who held his first post in the Reagan administration during the 1980s and served as secretary of defense from 2015 to 2017 in the Obama administration.

Ash Carter, U.S. Secretary of Defense (2015-2017); and Daniel E. Holland III ’79, P’07, ’08, Managing Director, Private Wealth Management, Goldman Sachs

“This is a guy I’ve known for a quarter century,” Carter said, speaking of Vladimir Putin. “It’s been eating at him all this time,” he added in reference to Putin’s long-held desire to annex Ukraine. Prompting his assessments and seated next to him on stage was Dan Holland ’79, P’07, ’08, a Goldman Sachs managing director and former Navy intelligence officer who remains active in national security issues. Holland also co-chairs the annual Finance Conference.

Though the invasion was no shock to him, Carter made it clear he was pleasantly surprised by the degree of Western resolve against Putin’s Russia. That happened only because the United States, armed with reliable intelligence, began “beating the drum” about Russia’s intentions three or four months before the invasion, according to Carter. He said those months gave Europe “mental processing time … It gave them time to get their spines stiff.”

In Carter’s assessment, the unified response of Western allies, including unprecedented sanctions against Russia, has bolstered the prospects of global stability by ramping up the costs of belligerence on the world stage. The sanctions, applied after the fact, could not have deterred the invasion but they will make it harder for Russia and other powers to contemplate similar behavior in the future, Carter said. Along that line, he also mentioned China and its well-known designs on Taiwan.

And what about the workers?

Meanwhile back in the states, the wages of average workers have been stagnating or growing ever-so slightly overall for around 50 years, even as corporate profits have soared. Conventional wisdom says the reason is that machines have replaced many workers, giving employers the upper hand. Assistant Professor of Finance Simcha Barkai, however, has discovered another factor: less competition and greater concentration within industries.

Simcha Barkai, Assistant Professor of Finance, Carroll School of Management

Barkai’s research on this matter has drawn notice in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and other banner outlets. During his remarks, he clicked on a stream of slides with data tables documenting the connection between industry concentration and labor’s declining share of the overall pie (during a period in which worker productivity has kept pace with the stellar performance prior to the 1980s, when wages steadily rose). Barkai stopped short of saying the trend is bad, partly because many good things have happened in the economy over the past half-century, having to do, for example, with efficiency and technological advances. He said possible remedies include making it harder for large corporations to merge, which would help reduce concentrations of corporate power.

One alumnus asked a question undoubtedly on many minds: How about the higher wages commanded by workers in the aftermath of the so-called “great resignation”? Barkai replied, “We don’t know if that’s a permanent effect or how much of it is COVID-related” and might change if millions head back to the workforce.

That may sound less upbeat than Paul Romer’s message kicking off the conference, but the Nobel laureate and self-proclaimed optimist cited one thing giving him pause. He voiced a deep fear that Americans are losing their belief in “the power of science, the value of fact, and the importance of expertise,” which he believes would upend the Enlightenment-inspired search for awe-inspiring ideas.

“We’re losing that sense, and nothing would be as tragic,” he said on a discomforting final note.